You are here

How ‘a city open to all’ was closed

By Sally Bland - May 03,2015 - Last updated at May 03,2015

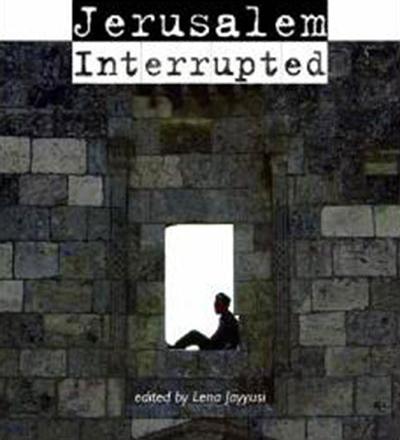

Jerusalem Interrupted: Modernity and Colonial Transformation 1917-Present

Edited by Lena Jayyusi

US: Olive Branch Press/Interlink, 2015

Pp. 500

Focusing on the city which many consider to lie at the heart of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, this book presents a panorama of real life in Arab Jerusalem, particularly during the British Mandate years — and how it abruptly changed in 1948. Comprising essays by 19 different scholars, “Jerusalem Interrupted” has in-depth coverage of a broad range of fields and issues, reflecting the diversity and development that was once a hallmark of the city. High-quality, historical and current photos and maps complement the well-researched essays. Taken as a whole, the book provides a comprehensive picture with a good balance between detail and general observation.

The first roughly two-thirds of the book addresses socio-cultural life in pre-1948 Jerusalem, with essays covering art, photography, music, radio, the press, attire, popular festivals, education, health, the women’s movement and childhood memories. Together, they present a nuanced picture of the complex demographic reality evolving in the city and its relations to the wider world. While the focus is on Palestinian development, due credit is accorded to foreign input in Jerusalem’s evolving modernisation; on the other hand, there is frequent critique of British colonial policy.

Many essays highlight the intersection — or collision — of cultural life and politics, in the highly charged situation created by the Mandate authorities’ support to the Zionist project. In one example, Awad Halabi traces how the traditional Nabi Musa festival changed as Palestinian resistance to British policy and Zionist encroachments grew; and how the celebration figured into Al Haj Amin Al Husayni’s leadership strategy. Equally fascinating is Ellen Fleischmann’s piece on Jerusalem Arab women’s politicisation. Tracing the sustained activities of the early women’s movement, which “transcended the more traditional fissures of class, religion and class”, she argues that their involvement was very political even when they worked under the banner of charity groups. (p. 154)

No matter the topic addressed, the essays depict Arab Jerusalem as a cosmopolitan city on the move, whose residents were open to diversity and aspired to advancement. It was also a regional crossroads: As pointed out by Samia Halaby, until the division of the area and the imposition of mandates, “Beirut, Jerusalem and Damascus had all been part of one country”. (p. 30)

Writing about childhood memories from that time, Rochelle Davis dubs Jerusalem “a city open to all”, where there was much mixing among different religious and ethnic communities

(p. 207)

The picture of social mixing is substantiated in a number of other essays, such as that by Elias Sahhab, recalling joint performances by musicians from different religious backgrounds. Diversity was also reflected in attire as Widad Kawar writes: “The material heritage of Jerusalem during the Mandate period is an expression of multiple coexisting worlds.” (p. 169)

The contrast could not be greater in the final portion of the book, which covers how these “multiple coexisting worlds” were severed from each other and the city closed off from its Arab environment by Israeli occupation policy. Based on interviews and oral histories, Thomas writes about how Palestinians and Israelis, respectively, remember their pre-1948 relations, highlighting the many mixed neighbourhoods that defied the British authorities’ delineations into strictly bounded communities. Nadia Abu El-Haj explores the physical impact of how archaeology is practised to “rearrange reality”.

Writing on “The Israeli Redefinition of Jerusalem”, Ahmad Jamil Azem analyses how Israeli policies since 1967, “and most sharply since the Oslo Accords… created the bizarre image of a city partitioned and crisscrossed by snaking walls and roads”, so that it is “impossible to describe Jerusalem now as a normal city”.

(pp. 326-7)

To redress the current situation where Palestinians are largely cut off from each other and from their capital, Nasser Abourahme contributes an essay entitled “Imagining a Just Jerusalem: Citizenship and the Right to the City”, concluding that “walls will not guarantee anyone a ‘quality of life’ — much less for Israelis who will end up ghettoising themselves in the shadows of overflowing Palestinian slums”.

(p. 365)

While there are many accounts of Palestine’s modern political history, it is only in recent times that the country’s social and cultural history has been properly addressed in English-language books. “Jerusalem Interrupted” is a substantial, new contribution to this latter type of history, which has rich political implications for understanding the past and working to chart a different future.

Related Articles

Falastin Al Hadara ‘abr Al Tarikh — Palestinian Civilisation throughout HistoryTranslated from the Arabic by Joud Halawani Al TamimiAmman: T

Gaza as a MetaphorEdited by Helga Tawil-Souri & Dina MatarLondon: Hurst & Company, 2016Pp.

Palestine: Memories of 1948, Photographs of JerusalemChris Conti and Altair AlcantaraTranslated from French by Isabelle LavigneLondon: Hespe