You are here

Deep roots of Palestinian culture

By Sally Bland - Dec 02,2018 - Last updated at Dec 02,2018

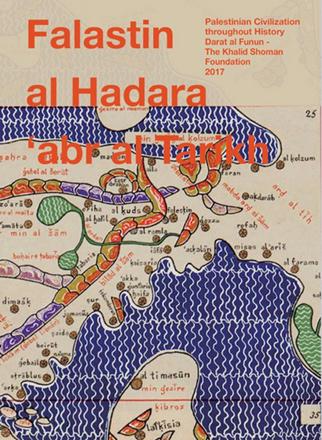

Falastin Al Hadara ‘abr Al Tarikh — Palestinian Civilisation throughout History

Translated from the Arabic by Joud Halawani Al Tamimi

Amman: The Khalid Shoman Foundation/Darat al Funun, 2017

Pp. 264

The year 2017 marked 100 years since the Balfour Declaration, 70 years since the UN Partition resolution and 50 years since the 1967 war. Instead of only lamenting these major injustices inflicted on the Palestinian people, Darat al Funun put together a comprehensive year-long programme showcasing the diversity and depth of Palestine’s pre-1948 culture via lectures, films, exhibitions and performances.

Published in Arabic and English editions, “Falastin Al Hadara ‘abr Al Tarikh” is a beautiful book containing the text of the lectures and many stunning photos of the exhibitions and other events. From the 12th century map of Syria, Palestine and Sinai on the cover to Ammar Khammash’s combining of music and geology into geo-acoustics in his exhibit “Desert Soundscapes”, everything in this book is valuable and previously underexposed. Since it would be impossible to cover all the contents, this review will concentrate on the lectures, all of which were delivered by experts in their fields who exhibited a high degree of original research and out-of-the-box thinking.

Viewing Jordan and Palestine as one civilisational unit, Moawiyah Ibrahim provides a truly long view of history by noting ancient human settlement in the area dating back before 10,000 BC, at sites such as Tel Al Sultan and Ain Ghazal. Several personal, cultural narratives bring the book up into the 20th century: Tamam Al Akhal tells the story of her exile from Yafa, and how she dedicated her art to the cause of Palestine. Widad Kawar discusses the interplay of continuity and innovation as seen in traditional Palestinian dress, based on her 60 years of collecting heritage items. Hisham Khatib revisits history from ancient times up to the 19th century, based on his extensive collection of maps, paintings, photos, travel books and valuable plates of the Holy Land.

Profiles of pioneering individuals give a nuanced picture of life in their times, such as Issam Nassar’s talk on Karimeh Abbud, the first Arab women photographer in Palestine. Nazmi Al Ju’beh’s lecture on outstanding members of the Khalidi family and how their efforts culminated in the establishment and preservation of the Khalidi Library in Jerusalem, despite the odds, documents the wealth of books and learning that existed in pre-1948 Palestine. Aida Najjar presents a comprehensive picture of the birth of the Palestinian press and how it served as the voice of the national movement in protesting British colonialism and Zionism. Based on original sources, i.e., the archives of early newspapers like “Al Karmil” and “Falastin”, her research goes beyond generalities to include many fascinating details.

Similarly, Faiha Abdulhadi’s lecture was based on original research, in this case, oral history interviews, that unearthed many fascinating facts about Palestinian women’s political participation from 1930 until 1948, including how they arrived at their political positions, how their politics surpassed mainstream nationalism and how it impacted on their personal lives.

Like many of the expert lecturers, Suhail Khoury’s talk on Palestinian music placed his topic in the context of Palestine’s Arab identity: “Historically speaking, there is no such thing as Palestinian music… there is Arab music and oriental music”. (p. 138)

Following developments up to the present, Khoury shows how this changed somewhat in the early 20th century as missionary schools spread the influence of European music, and the subsequent occupation of Palestine interjected new political themes.

The most provocative lecture was delivered by Khaldun Bshara on Palestinian heritage, in which he analysed both the colonial destruction inflicted by Israel and the dilemma faced by Palestinians who are forced into reductionist battles such as who invented falafel. He contended that “as far as Palestinians do not regard heritage as modes of life and as modes of knowledge production at the local level, Palestinian heritage will undergo further ‘falafelisation’, and also risks the loss of the transnational global dreams”. (p. 160)

Mohanad Yacoubi gives an interesting view on modernity in Palestine at the beginning of the 20th century, especially as related to filmmaking, while Qais Al Zubaydi presents a history of Palestinian cinema. Salim Tamari approaches modernity from a literary angle, exploring fictionalised autobiographies produced in the time of transition from Ottoman to British rule, particularly the writings of Najib Nassar, founder of “Al Karmil” newspaper.

Of course, the events of 1948 intrude into virtually all of the year-long programme, but it was the special focus of two screenings. One was Rawan Damen’s film series which doesn’t confine itself to one year but is titled: “The Nakba 1799 — 2008”. The other was a lecture by the respected scholar, Walid Khalidi, who also stressed the Nakba as an extended, on going process. Also screened was a little-known film directed by Edward Said, “The Shadow of the West” (1986).

“Falastin Al Hadara” is a book to savour for its beauty and to read for the knowledge it imparts. With its publication, Darat al Funun sets an important example of how commemorations can and should be used to broaden one’s horizons, enhance one’s aesthetic and humanist instincts, and bolster resistance to injustice.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Palestinian cultural heritage on Saturday was brought to life in a musical performance by the renowned traditional folkloric group A

AMMAN — Two women. Two films. Two angles on Palestine’s past, present and future.

AMMAN — Darat Al Funun-The Khalid Shoman Foundation recently received the Jerusalem Award for Culture and Creativity in the Arab world, in r