You are here

The threat of Israel boycotts more bark than bite

By Reuters - Feb 23,2014 - Last updated at Feb 23,2014

OCCUPIED JERUSALEM — Though voices are getting louder inside and outside Israel about the threat of economic boycotts for its continued occupation of Palestinian territories, there seems little prospect of it facing measures with real bite.

With a number of European firms already withdrawing some funds, Israeli Finance Minister Yair Lapid has warned that every household in Israel will feel the pinch if ongoing peace talks with the Palestinians collapse.

US Secretary of State John Kerry has also warned that Israel risks a financial hit if it is blamed for the failure, but investors and diplomats say they are unconvinced.

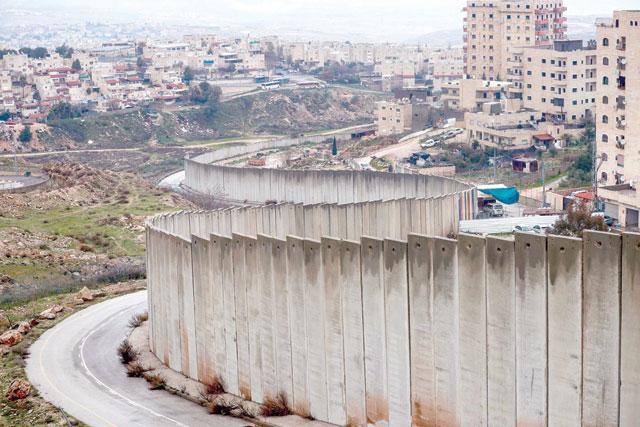

It is true that some foreign firms have started to shun Israeli business concerns operating in East Jerusalem and the West Bank — land occupied in the 1967 war — and the European Union is increasingly angered by relentless Jewish settlement expansion.

But the bulk of Israeli business is clustered on the Mediterranean coast, a world away from the roadblocks and watchtowers of the West Bank, and not even the Palestinian leadership is demanding a total economic boycott.

“The boycott is being used like a bogeyman, a scary story you tell a child at night,” said Jonathan Medved, CEO of OurCrowd, a crowdfunding platform looking to provide venture capital to Israeli companies.

“The truth is that Israel is a world leader in water technology, next-generation agriculture, cybersecurity, healthcare innovation and start-ups. What sane person is going to walk away from that?” he said, speaking by telephone during a visit to South Africa to seek out potential partners.

Europe stirs

Embargoes, sanctions and boycotts, along with internal resistance, helped bring about the isolation and eventually the end of apartheid in South Africa in the 1980s.

Pro-Palestinian, or anti-Israeli, activists hope to use the same tactics to force Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to sign a deal to create an independent Palestine based on the 1967 borders. They believe recent action by a handful of European firms to distance themselves from Israel might be the start of something big.

In December, Dutch firm Vitens said it would not work with Israeli utility company Mekorot because of its West Bank footprint. The following month a large Dutch pension fund, PGGM, ended its investment in five Israeli banks because of their business dealings with settlements considered illegal under international law. Denmark’s Danske Bank blacklisted Bank Hapoalim for the same reason.

These moves sent a jolt through the Israeli government.

“If the negotiations with the Palestinians break down and a European boycott begins, even partially, Israel’s economy will go backwards, every person will be directly affected in their pockets,” Lapid said in a speech earlier this month.

Unlike some of his Cabinet colleagues, the finance minister supports the need to pull back from much of the occupied territories in an effort to secure an elusive peace accord.

Looking to convince the sceptics, Lapid said failure to strike a deal could lead to a 20 per cent drop in exports to the European Union and a halt in EU direct investment, warning that this would cost the Israeli economy 11 billion shekels ($3.1 billion) a year.

Supporting his case, Lapid points to an EU decision last summer to bar financial assistance to any Israeli organisations operating in the West Bank, and warns this could be expanded.

But EU diplomats say business with firms operating in the settlements, such as skincare company Ahava, represent less than 1 per cent of all Israeli-EU trade, which last year totalled $36.7 billion, up from $20.9 billion a decade earlier.

The European Union matters because it is Israel’s largest trading partner and it is the only place where murmurings of sanctions have so far been raised outside the Arab world, where only Egypt and Jordan have formal ties with Israel.

However, Europe is not united on how to deal with Israel and has not yet even agreed to introduce EU-wide labelling to make clear if goods come from settlements, much less anything more radical along the lines suggested by Lapid.

“There is no EU boycott,” the president of the European parliament, Martin Schultz, said this month during a visit to Jerusalem during which he questioned whether the 28-nation bloc would want to penalise Israel if the US-backed talks failed.

EU governments say it is up to each firm to decide its own investment strategy.

While a handful of states, including Britain, Germany and the Netherlands, discourage links with the settlements, there are no consequences for ignoring that steer, beyond the “potential reputational implications” a British Foreign Office agency warns of on its website.

Schultz said he was “not convinced about economic pressure”, and also cast doubt on the need for clear labelling of settlement goods that would allow consumers to chose.

“Does it carry such a large weight that it could really change something?” he asked reporters.

Divestment

The international Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement seeks something much more emphatic, eager to turn all Israeli brands into toxic property as a way of forcing the government to roll back settlements and sign a full peace deal.

Omar Barghouti, the BDS co-founder, told Reuters he sensed a changing international atmosphere and was particularly buoyed by news of divestments from Israeli banks.

“We’re talking about a completely different league here. Forget boycotting settlements, [that is] peanuts. Targeting the banks, that’s where the money is, that’s the pillar of the Israeli economy,” said Barghouti.

However, divestment moves by the likes of Danske Bank appear to be the exception rather than the norm.

Germany’s biggest lender Deutsche Bank AG denied reports last week that it was set to boycott Israeli banks, while the giant Dutch pension fund ABP announced this month that after a review, it saw no need to cut ties with Israeli banks.

All the while, foreign firms continue to pour into Israel. According to the latest Bank of Israel data, direct investment was $10.51 billion in the first nine months of 2013, up from $9.5 billion for the whole of 2012. Exports to Europe rose 6.3 per cent last year.

Global brands such as Google, Cisco, Microsoft, Twitter, Apple, AOL and Facebook have all invested in Israel, so, like it or not, users of computers, smartphones and apps could well be supporting Israeli engineering.

“All the talk about boycotts has not so far caused any damage to our economy,” Uriel Lynn, president of the Israeli Chambers of Commerce, told Reuters.

“Israel has gone through much harsher boycotts in the past. For example, we did not have commercial relations with China for years, and for a time we could only buy crude oil from Mexico and Egypt. So we can definitely withstand boycotts.”

Related Articles

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu met with three of his top ministers to discuss ways to deal with the threat of economic boycotts against Israel, media reported Monday.

An international campaign to boycott Israeli settlement products has rapidly turned from a distant nuisance into a harsh economic reality for Israeli farmers in the West Bank’s Jordan Valley.

WASHINGTON — US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on Thursday denounced the UN release of a list of companies involved with Israeli settlements