You are here

Khomeini: father of Iran's Islamic republic

By AFP - Jan 30,2019 - Last updated at Jan 30,2019

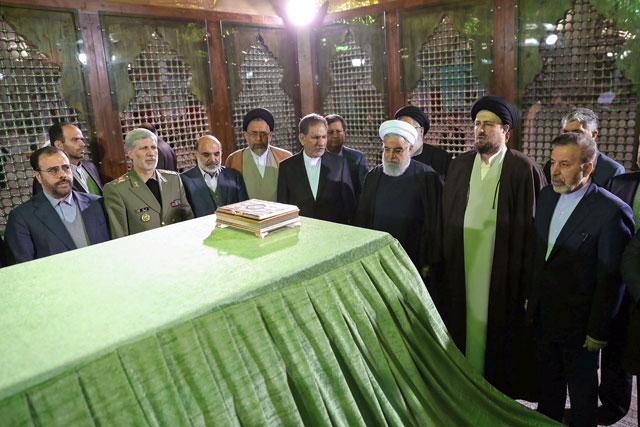

Iran's President Hassan Rouhani visits the shrine of the founder of the Islamic republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, south of Tehran, Iran, on Wednesday (Reuters photo)

TEHRAN — Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was an austere and charismatic cleric who became an icon of the 20th century for standing against the West and bringing down Iran's monarchy, but also for his revolutionary ideas about Islam's role in politics.

The black-turbaned Shiite scholar spent more than 14 years in exile before returning to his homeland at the age of 76, two weeks after mounting protests forced the shah to flee into his own exile.

Religious scholar

Ruhollah, whose name means ‘‘spirit of Allah’’, was born in 1902 to a family of religious clerics in Khomein in central Iran, and later adopted his hometown's name.

He was only a few months old when his father was murdered because of his opposition to the imperial regime.

Brought up by his mother and aunt, he undertook religious studies, notably in the holy city of Qom, south of Tehran.

In 1929 he married a 16-year-old girl with whom he had three daughters and two sons.

He mastered philosophy along with Islamic law and jurisprudence and started teaching, gaining a reputation for his knowledge and moral rigour.

He also studied less traditional aspects of Shiism, including the mystical strain of ‘‘erfan’’, and composed his own poetry.

By the late 1950s he was being considered an ayatollah, which means ‘‘sign of God’’ and designates a high-ranking Shiite cleric, though he found himself increasingly at odds with a religious establishment that preferred to stay out of politics.

Khomeini became a fierce opponent of the pro-Western shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, particularly over a series of agricultural and social reforms that threatened the land-owning elite and their clerical allies and sought to grant women the right to vote.

Jailed and exiled

In an inflammatory sermon in 1963, Khomeini warned the shah that he risked being overthrown by the people if he continued along his reformist path — a speech that led him to jail.

A year later, he was forced into exile following a vehement outburst after the shah had given diplomatic immunity to US military personnel.

He went first to Turkey and then to Iraq in 1965, where he set up base in the Shiite holy city of Najaf.

It was here that he evolved his doctrine of ‘‘velayat-e faqih’’ (‘‘the guardianship of the jurist’’), declaring all forms of monarchy unjust and stating that political leadership should be in the hands of religious judges as the only people with the authority to interpret and implement divine law.

Expelled from Najaf by Iraqi authorities, Khomeini moved to France in 1978, leading the last stages of the Islamic revolution from a Paris suburb.

His fierce diatribes against the shah were recorded on cassettes and smuggled into Iran, where the bloody repression of demonstrations was bringing ever larger numbers of people into the streets.

As the protests grew, the shah fled Tehran on January 16, 1979. And on February 1 ‘‘the flight of the revolution’’ brought Khomeini back in triumph. The Islamic republic was proclaimed on April 1.

‘The Great Satan’

Throughout the 1970s, Khomeini adopted some of the left-wing rhetoric popular among students and activists, defining the anti-shah movement as one of oppressed masses taking on a tyrant.

In this, he could draw on centuries of Shiite symbolism around martyrdom and resistance that gave his message mass appeal.

He had another priority: ousting the United States — a former ally of the shah — which he labelled the ‘‘Great Satan’’.

In November 1979 radical student followers of Khomeini held 52 American diplomats and citizens hostage at the US embassy in Tehran for 444 days. Although it was not immediately directed by Khomeini, he saw an opportunity to ensure the revolution maintained its radical direction, and relations with Washington have never recovered.

At the end of 1979, Khomeini was made the ‘‘leader’’ (‘‘rahbar’’) after the new constitution of the Islamic republic of Iran was enacted, based on his doctrine of velayat-e faqih.

A rapid process of Islamisation was thrust upon Iranian society — and the revolutionary fervour was viewed with concern by neighbouring dictators.

‘Satanic Verses’ fatwa

In 1980, Iraq's Saddam Hussein sought to exploit the upheaval in Iran and launched a war to seize territory and prevent the spread of the revolution among his own majority-Shiite population.

Iran's nascent revolutionary government put up a surprisingly effective defence, but was dragged into eight long years of conflict before Khomeini reluctantly accepted a ceasefire.

The nation was devastated by the conflict, but it greatly strengthened the Islamic system, which triumphed over Marxist and liberal internal opponents.

Weakened by prostate cancer, Khomeini issued a fatwa — a religious edict — shortly before he died on June 3, 1989.

He called for the death of British writer Salman Rushdie for the novel ‘‘The Satanic Verses’’, which the ayatollah considered blasphemous — ensuring the Islamic revolution remained a defiant challenge to the West.

Related Articles

TEHRAN — Iran’s first president after the 1979 Islamic revolution, Abolhassan Banisadr, died in a Paris hospital on Saturday aged 88, after

ANKARA — The death of former president Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani deprives Iran’s reformers of a powerful ally, boosting anti-Western hard

DUBAI — Hundreds of thousands of Iranians marched and some burned US flags to mark the revolution's 40th anniversary on Monday as Tehran sho