You are here

Treasures of Khirbet Ain: Unveiling history through dolmens, pottery

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Jan 29,2024 - Last updated at Jan 29,2024

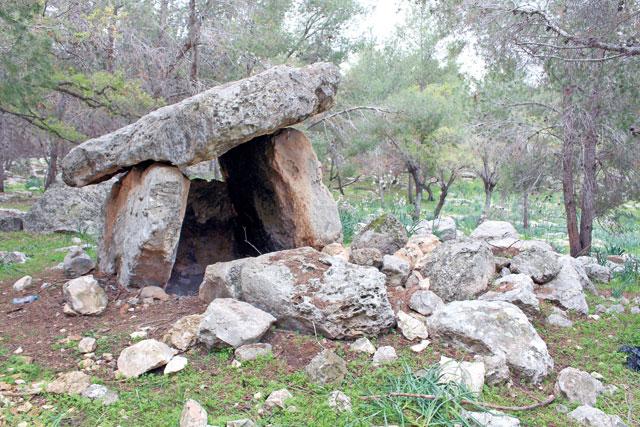

A Khirbet Ain tomb (Photo courtesy of APAAME)

AMMAN — Between Jerash, Mafraq and Zarqa lies a modern village named Khirbet Ain, located seven kilometres away from the well-known centre of Rihab. The valleys have good arable soils and although the hills are generally barren and have little soil cover, the lower slopes are often cultivated with cereals or fruit trees. Due to a relatively enough rainfall, Khirbet Ain and its vicinity is irrigated enough to support local agriculture.

The area was occupied before the Bronze Age, which is attested by its visible dolmens. The periods of the extensive settlements were the Late Bronze Age and the Roman-Byzantine period (1st century AD and 7th century AD).

“Travellers passed by to the west through Jerash or to the east along the line of the Pilgrim Road [and later the Hijaz Railway]; the route from Jerash to Mafraq has only become important in relatively recent times, and even the likely Roman road has not been traced,” mentioned Emeritus David Kennedy from The University of Western Australia, adding that despite its growing population and development in recent years, this area has not been explored by scholars.

American archaeologist Nelson Glueck was at Khirbet Ain in 1944 during one of his tours around the Holy Land.

“The site lies in a valley running roughly east to west through which flows, seasonally, the Wadi Al Ulari. The Wadi Ain joins it from the north, downstream of the modern village of Khirbet Ain. The combined wadi later acquires further tributaries and, as the Wadi Khuraysan, flows into the Wadi Zarqaten, kilometres to the southwest,” said Kennedy, who is one of the pioneers of the aerial archaeology.

The Tell (hill) lies on the southern side of the Wadi Al Ulari, opposite the village and south of the “strong spring”, which has drawn settlement throughout the ages and given its name to the modern village, Kennedy continued, adding that the photograph shows an oval mound with terracing on the northwest side and lower earthworks to the west.

Pottery found in the site originates from the Chalcolithic, Early Bronze Age and Roman-Byzantine periods.

“Most of the finds are from the Iron Age,” Kennedy said, noting that it may be that the buildings of the ancient village were partially cut into the hillside.

No date has been proposed yet, but Roman to Early Islamic seem most likely on the basis of the dominant material remains of the site apart from the Tell, the archaeologist underlined.

Another Australian archaeologist, Ina Kehrberg, analysed sherds from the site, dating them to the Hellenistic (1st century BC), Late Roman (3rd century AD), Late Byzantine (7th century AD), Mamluk (13th -15th centuries AD).

“Qasr Ain might have had a monastic phase,” speculated Kennedy, but there is no sufficient evidence.

This research has discovered Khirbet Ain and its vicinity as a significant and archaeologically rich area. There is a possibility that Khirbet Ain was a Roman military site on the ridge, underlined Kennedy.

Because of a classical tomb, Kennedy continued, there is a probability that a rich individual was buried there and that he was a landowner.

“Khirbet Ain was never on the same scale as Rihab, with its numerous churches, monuments and structure, but it was probably typical of many of the attractive small valleys of the region, and we might profitably search more widely to develop an understanding of settlement history in the region,” Kennedy explained.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The modern village of Khirbet Ain is located some seven kilometres southwest of Rihab, a hilly area with seasonal springs accessible

AMMAN — Metal production has always been part of human culture and never ceased completely at any historical period, according to scholar Mo

AMMAN — Dolmens, above-ground tombs made of giant slabs of stone, are scattered throughout northwest Jordan, but their absence from other ar