You are here

Syrian refugees in urban areas struggle to meet ends as pandemic crisis bites

By Serena Bilanceri - Jan 04,2021 - Last updated at Jan 04,2021

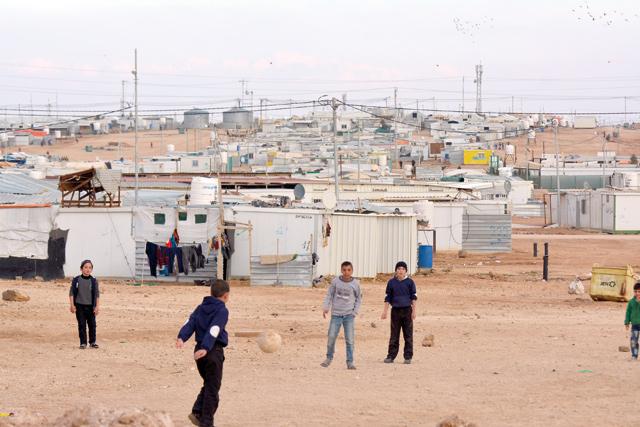

Children are seen playing football in the Zaatari refugee camp, some 80km northeast of Amman, in this photo taken on January 28, 2018 (Photo by Amjad Ghsoun)

AMMAN — A caravan of approximately 12 square metres is what Shawkat, his wife and his three children have been calling home for the past eight years. “I added another room outside to block out the dust and use it as a living room,” he said.

The 25-year-old Syrian refugee lives in Zaatari, some 80km northeast of Amman, the largest refugee camp in the Middle East according to UNHCR, home to more than 78,000 persons.

Shawkat, who had started to work as a photographer in his father’s studio in the southern Syrian province of Daraa before the war hit, is volunteering as a photographer in the camp now.

“The money is not enough to cover everything, but it is OK. I get paid something and it helps,” he said.

But refugees not participating in paid volunteering programmes now face bigger challenges, as they can no longer leave the camp to work due to the coronavirus safety measures, he added.

“The main thing that has impacted refugees is that their movement has been stopped. Previously, they were granted work permits and used to go in and out of the camps, but in March, this has stopped. Therefore, we have seen an increase in debts and borrowing," said Lilly Carlisle, spokesperson of UNHCR Jordan.

According to the UNHCR, nearly 14,000 refugees in Zaatari hold active work permits. This amounts to some 40 per cent of the adult population in the camp. And they have been greatly impacted by the COVID-19 measures, NGOs note.

The only money they now get is through NGOs and the UN, or if they have somebody on the outside who can send them money, said Shawkat.

Regarding changes that occurred in the Zaatari camp since the outbreak of the pandemic, Shawkat said: “The camp's main gate is closed, transportation in and outside the camp has stopped. People are going less to the market, because they do not have income to spend on buying things. In addition, students have experienced some issues with distance learning because the network is weak, and the connection is not stable for everyone.”

Yet the situation of many refugees living in the camps could be described as privileged, when compared to those refugees residing in Jordan’s bigger cities.

As different NGOs stated, many refugees who live in urban areas have been hit harder by the pandemic.

“To me, the situation of refugees who live in urban areas like Amman or other cities is much worse. Because they have to pay their rent, whereas in the camps shelter is provided for free. We have seen an increase of 30 per cent in the amount of refugees who get evicted,” said Carlisle.

Amal (not her real name) voiced her worries about the possibility of eviction of her and her family from their rented home. The 54-year-old woman arrived from Damascus to Jordan seven years ago and since then had lived in Amman with her husband and three of her children.

Her husband, she said, suffered a heart attack six years ago and can no longer work. So she started working part-time in a social enterprise that trains Syrian refugee women in handicrafts.

Amal, speaking about her income and rent cost, said that about JD150 comes from the activity at the handicraft centre, where she makes traditional soap, clothes and ceramic dolls. The rent costs her family JD280.

“One of my sons, who is married, is helping us. But it is getting harder: In the last five months, we were not able to pay the rent. The landlord said that he is going to kick us out of the house,” she said.

Her son, a daily worker, started to find fewer job opportunities during the pandemic and is no longer able to support his parents. As refugees, the family receives assistance from the UNHCR, which helps them to buy food.

When asked about future plans, she shook her head and said: “Only God knows.” Going back to Syria is not an option, as the apartment where she used to live was bombed.

“When the house collapsed, we decided to travel to Jordan. We were scared for our children,” she noted, “before the war, we used to live a comfortable life. We had our own house and my husband was working in a shipping company".

She added that she has been well-received in the Jordanian community, but the lack of money, which has increased after the pandemic, is making her life in a new country difficult.

The UNHCR spokesperson confirms that families in need who live outside the camps can receive financial aid. The monthly average for a family of four amounts to $180, nearly JD130.

After the pandemic, the UNHCR granted cash assistance to 52,000 additional refugee families. However, more funding is necessary. “We have a lot of refugee families calling us and asking why they have not received cash assistance. They do not understand how we choose them. The simple answer, sadly, is: We know that vulnerability has increased and more refugees are living in poverty, but we do not have the money to help them,” Carlisle said.

In camps, families receive additional cash for heating and winter expenses. Health and education services are provided on site. Refugees in the cities can access the national health system, Carlisle noted.

“At the moment, our health funding is very low, so we can only really cover the absolute emergencies. Refugees with non-emergency procedures will have to wait,” she added, noting that about 8,000 refugees are currently on the waiting list.

Nabila (not her real name), Amal’s colleague, said that she and her family prefer not to go to the doctor, even if they are sick, because they cannot afford the costs of treatment.

Impacted by the pandemic, the health situation of her husband deteriorated all the while job opportunities diminished, making her the sole breadwinner for a family of six, so debts began to accumulate.

“When the pandemic started, everything became more difficult,” she said. Three of her children are still underage and, after the school closures, they are learning from home.

“Online classes are really hard for them. We could not afford to buy a laptop … we borrowed one from the office here,” she said.

In Amman and Mafraq, Syrian refugees recount similar problems. Economic Recovery and Development Programme Manager at the International Rescue Committee (IRC) in Jordan Mohammed Alshdaifat pointed out that, since the beginning of the pandemic, many refugees who had received IRC grants to open a business, had to close them down because they could no longer pay the rent or buy raw materials, as they were no longer getting income.

“Sometimes we had a shortage of medications, especially inside the camps,” he added.

The organisation, which runs various programmes for health services, economic recovery, women and youth empowerment of Syrian refugees as well as Jordanians in need, stressed that refugees outside of the camps suffered mostly of lack of support to pay rent and food.

“And once distance learning began, for many children education has stopped,” Alshdaifat said, because their families could not afford an Internet connection or electronic devices.

“Definitely the economic impact of COVID-19 is what has had the worst impact on the refugees,” noted Carlisle, since “many of them relied on the daily work and the informal economy before the pandemic hit".

She also said that Syrian refugees can obtain work permits in some sectors, such as the construction, manufacturing or agricultural sectors, but many of them end up as gig workers with no contracts — mostly as cleaners and manual labourers, which "puts them at an additional risk”.

Around 80 per cent of the refugees were already living below the poverty line prior to the crisis, Carlisle noted.

According to a new report of the World Bank and the UNHCR, poverty among Syrian refugees in Jordan has increased by 18 per cent since the beginning of the pandemic. More than 90 per cent reported reducing meals or expenses for health and education, to cope with the situation.

“Statistics showed that 40 per cent of the refugees had lost their daily jobs because of the pandemic. In September, the statistics improved slightly, but I think that the long-term outlook is not great,” she added.

According to the report, it will probably take one to two years for the situation to recover.

Amal does not want to lose hope, but the economic hardships are making it difficult for her family to picture a bright future here. "My children are thinking about travelling abroad, and if I get a chance, maybe I will as well."

Related Articles

AMMAN — In 2021, approximately 5,800 refugees returned from Jordan to Syria, which took place on a voluntary basis, independent of UNHCR, ac

AMMAN — The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Jordan Hashemite Fund for Development (JOHUD) recently began engag

AMMAN — Following a surge in donor activity over the last month, the UNHCR’s 2019 operations in the Kingdom are 44 per cent funded as of the