You are here

Political networks in Eastern Mediterranean during Late BA

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Jul 30,2024 - Last updated at Jul 30,2024

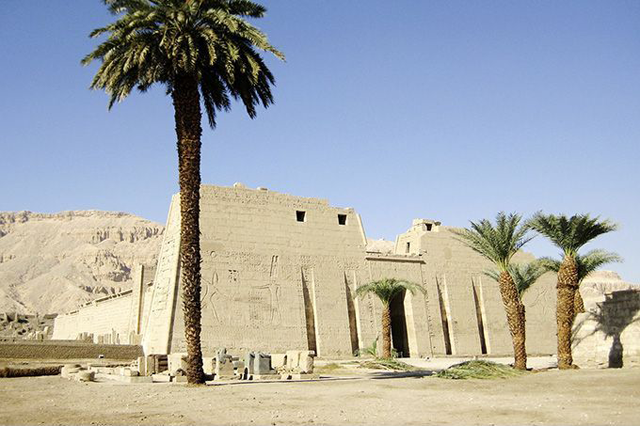

A sacrificial altar in Arad, a Bronze Age centre located near the Dead Sea (Photo courtesy of ACOR)

AMMAN — The Late Bronze Age was a period of connectivity between different political centres in the Middle East, North Africa and southern Europe. The political and cultural collaboration thrived between Hittite, Babylonian, Egyptian and Assyrian states.

The regions of Europe, Mycenae and Crete also had a complex trade and political relations with these kingdoms and their satellites. Archives found in Anatolia, Syria, Egypt and Greece testify about a sophisticated correspondence and establishment of the Mediterranean political order.

The terminology of the time reflects in a way kings referring to each other as "brothers" while their subordinates were called "sons".

"The resulting political system in the Near East during the Late Bronze Age consisted of a double level of political rule with a hierarchical system of large regional units based on a higher level of 'great kings', and a lower level of 'lesser kings' who were bound by treaties to rulers of empires," said the professor Ann Killebrew from The Pennsylvania State University, adding that throughout the Eastern Mediterranean region, political and economic power was concentrated in the palace.

The palace complex served as the administrative centre and seat of the local ruler located in urban settlements, while in the case of the "small kings", the palaces' control extended to the respective surrounding hinterland, or periphery.

"The same centralised system could be used by the 'great kings' of Egypt and Hatti to administer an empire, with the smaller urban centres serving as the hinterland to the major centres.

Economically, the palace system was characterised by monopolistic production and intensive interregional trade, "Killebrew said, adding that the closely interrelated political and economic structure of the Eastern Mediterranean region during the 13th century BC is reflected in the material culture which is characterised ceramically by mass production and standardised ceramic vessels, especially observable in the homogenous ceramic repertoire of Canaan proper.

In the Syro-Palestinian region, she continued, the double level of political rule was particularly evident because of the numerous small semi-autonomous kingdoms, each with local dynasties. Greater Canaan was divided between the two major powers of the region following the battle at Kadesh on the Orontes River in 1,285 BC.

Northern Canaan (Syria) was mainly under Hittite influence, while southern Canaan (Palestine) was under Egyptian political control.

Furthermore, "Based on Egyptian and Hittite texts, it is evident that the administrative style of the two major powers differed. The Egyptian vassal states had well defined obligations, while Pharaoh had few. The goal of the Egyptians was the prevention of rebellion and the extraction of tribute," Killbrew said.

Hittite treaties with vassal states indicate a more mutually beneficial relationship, with clearly defined Hittite obligations to its vassal states.

Mycenaean Greece, if in fact is Ahiyyawa of Hittite diplomatic correspondence, may have had a "Great King", who is referred to as a "brother" in Hittite texts.

"However, the archaeological and Linear B textual evidence does not seem to support the claim of one major centre which united Mycenaean Greece under a single charismatic political and divine leader," the scholar underlined.

On the contrary, Mycenaean Greece was politically heterogeneous and city-states often waged wars against each other.

According to Killbrew, the Aegean region and, at most times, Cyprus seems to be autonomous mini-powers not united under one great king.

"Their main interest in the east was economic, evidently due to their very lucrative international trading and raiding ventures in the Eastern Mediterranean. Moreover, the textual and archaeological evidence suggests that the political and economic structure of mainland Greece and the Aegean islands differed from the empire oriented Near East," Killbrew said, adding that when the meltdown of the great centres of power began in the 13th century BCE, the concentration of political and economic power transformed the physical collapse of the palace system into a general disaster for several of the larger regional powers.

On the other hand, the decline or collapse of the "superpowers" liberated many of those areas under their control and, presumably, exploitation. The breakdown of international lines of communication between the empires was replaced by more local lines of communication and resulted in the fragmentation of Canaan into smaller regionally-defined units.

Egypt was the major political force in Levant during the 13th century BC, and the later appearance of regionally defined material cultures in Canaan during the 12th century BC must be understood within the framework of the political and economic decline of Egypt in Canaan during the 20th Dynasty of New Kingdom Egypt.

"Late Bronze Age Cyprus played a key role in the international trading network, providing the link between the Levant and the Aegean," Killbrew noted, adding that 12th century BC developments on Cyprus, on coastal Anatolia (especially Cilicia) and in the Dodecanese, were a result of the decline and collapse of the Mycenaean and Hittite empires.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Due to its geographic location, Cyprus played a significant role in trade during the Late Bronze Age.

AMMAN — The Late Bronze Age collapse brought a dramatic societal change in the Southern Europe, North and South Levant.

The assembly of over 3,000 stones — in natural shades of beige, red and black, and arranged in triangles and curves — was unearthed in the remains of a 15th century BC Hittite temple, 700 years before the oldest known mosaics of ancient Greece.