You are here

‘Old-fashioned views’ affect study of Frankish presence in Petra — Italian scholar

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Apr 23,2017 - Last updated at Apr 23,2017

AMMAN — Academics have often relied on “old-fashioned views” when it comes to understanding the Crusader period, and these views have also affected the study of the 60-year Frankish presence in Petra, according to an Italian archaeologist.

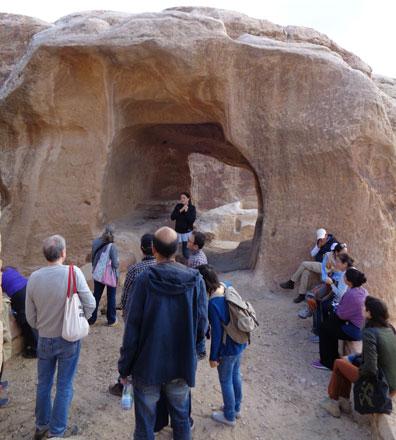

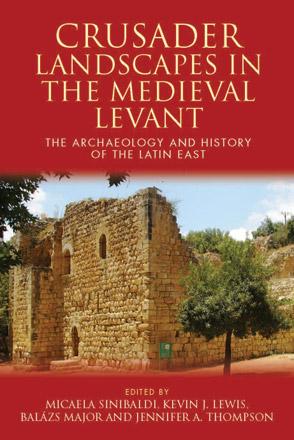

At the launch of the book “Crusader Landscapes in the Mediaeval Levant. The Archaeology and History of the Latin East”, held at The Jordan Museum on April 17, Micaela Sinibaldi elucidated on the Frankish presence in this part of the Middle East.The event was the first partnership between the British Institute in Amman and the Jordan Museum.

Sinibaldi described how the case study of Crusader-period Petra has resulted in new conclusions, which are important for understanding both the Crusader period in Petra and later phases at the site.

“According to a traditional view, the Europeans brought deep changes to the society in Petra, which was more or less abandoned after the Byzantine period, apart from a parenthesis of important revival during the brief Crusader-period phase,” she said.

“This phase saw a great increase in population and trade with Palestine,” the scholar noted, adding that these theories also state that the Frankish population was mainly located at the bottom of the Petra Valley, from where trade through the Wadi Araba could be best controlled.

Moreover, according to these theories, the Petra settlements were founded before Shobak Castle, of which they were more important, the expert underlined, adding that an analysis of both documentary and archaeological sources leads to very different conclusions.

“The sources state clearly that the settlements in Petra were only founded around 1130/1140 AD, after Shobak Castle (1115 AD), which was beyond any doubt the most important site of southern Transjordan in the Crusader period, before Karak Castle was constructed in 1142 AD,” the scholar explained.

Additionally, the hypothesis according to which Petra was connected to important trade networks within the Naqab trough the Petra Valley is not supported by the ceramic record, Sinibaldi stressed.

“Instead, both the documentary sources and the ceramic record support the interpretation that it was through Karak, Shobak and the Darb Al Haji, the mediaeval pilgrim’s road to Mecca and Medina that Petra received imports from the western parts of the Latin Kingdom,” she argued.

Both documentary sources and archaeology have also shown that the Frankish settlements were mainly located not inside the Petra Valley, but outside of it, where they could best take advantage of opportunities for security, water and agriculture, she said, noting that “ cultivation had a very high potential on the western slopes of the Shara mountains”.

Finally, the Crusader period had a relatively low impact on the community of Petra at the time, Sinibaldi claimed; a recent study of ceramics she has conducted in Petra proves that settlement in this area “did not have significant gaps during the Islamic period, and the 12th century does not at all appear to be characterised by a substantial increase in population or trade, to be followed by a sudden decline thereafter”.

This is consistent with the historical sources , which suggest that in the Sharat Al Jibal the Franks introduced themselves into an already burgeoning economic prosperity that had begun in the 11th century and for which they were not mainly responsible, Sinibaldi added.

The archaeologist sees the origin of the incorrect thesis that Crusader-period settlement was focused on the Petra Valley also in the fact that archaeological research has been largely centred on the valley itself, but much less on the hinterland.

“An image of Petra as abandoned during the Byzantine period, apart from a short parenthesis during the Crusader period, to be rediscovered to the West by Burckardt in 1812, is often found in general guidebooks or magazines,” she underscored, adding that it “ appears to have also originated from a combination of the great importance of the valley during the Nabataean period and by a European-centred view, which saw the Crusader period as always bringing deep changes to the Middle East”.

Furthermore, this image has been combined with the common one of Crusader Transjordan as the southeastern frontier of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, consisting mainly of a series of fortified points to defend a border, the archaeologist explained.

“This limited interpretation has led scholars to neglect the aspects of rural settlement and patterns of continuity and adaptation, and focus on those of change and disruption, which do not correspond to the evidence from the sources; in fact, the Franks had to rely substantially on good relationships with the local populations, which were essential to their survival in the region,” highlighted Sinibaldi.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The Late Petra Project focuses on a settlement in the Petra region occupied after the Byzantine period, ca.

AMMAN — A group of 10 foreign archaeologists recently concluded a tour of little-known Crusader-era sites in Jordan to learn more about the

KARAK — By analysing the architecture and historical documentation, it is possible to reconstruct a detailed history of the Karak Castle dur