You are here

Neolithic hub of Ain Ghazal: Delving into urban transformation through artefact, bone studies

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Apr 24,2024 - Last updated at Apr 24,2024

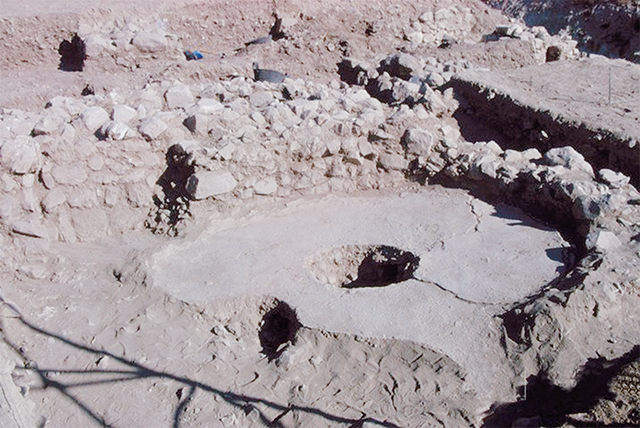

A circular shrine at Ain Ghazal in north-eastern Amman (Photo courtesy of ACOR)

AMMAN — The settlement at Ain Ghazal Site is one of the largest Neolithic settlements known in the Near East and is situated on the western edge of the Wadi Zarqa, which, although dry today, was a permanent stream from at least late Pleistocene and early Holocene times until the mid-1950’s. Ain Ghazal is now part of north-eastern Amman.

According to the American scholar Gary Rollefson, Ain Ghazal was “a Neolithic Manhattan”. Unfortunately, significant part of the site was destroyed during the construction of the Amman-Zarqa highway, the construction of railway and the sewer treatment plan.

“The preserved portions of Ain Ghazal, with positive evidence of architectural construction, cover a total of 12-13 hectares,” Rollefson said, adding that other sites from the same period like Beidha, Tell Abu Hureyra in northern Syria and Beisamoun and Khirbet Sheikh Ali, in northern Palestine, were all smaller.

Definitions of significant changes in cultural phases in the Neolithic period have traditionally relied on recognition of a number of alterations in subsistence economy and both technological and typological changes in artifact manufacture, although other aspects of lifeways can also be used to define such distinctions.

Nevertheless, the massive disturbance and subsequent mixing of earlier cultural deposits by later inhabitants at Ain Ghazal (and other Neolithic settlements) renders some of the phase distinctions suspect, Rollefson underlined, noting that because of the substantial nature of Neolithic architecture, there is less opportunity for confusion in the archaeological record of cultural changes, and the general history of Ain Ghazal is represented better.

There is more than a half-million animal bone fragments at Ain Ghazal, but only a small fraction (ca. 50,000 specimens to date) are identifiable to species, genus, or even “kind” of animal.

“Much of this enormous amount has not yet been analysed principally because of the overwhelming volume of material and the condition of preservation; the latter situation is particularly the case for the PPNC and Yarmoukian samples: In these phases animal bone is characteristically covered with a thick encrustation of lime deposits that hampers analysis,” Rollefson said.

Nevertheless, a well-defined sequence of developments in animal exploitation is available for most of the cultural sequence at Ain Ghazal.

According to Rollefson, goats were domesticated by the end of the Mid-Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period, based on culling patterns and metrical analysis. During this phase of the Neolithic at Ain Ghazal, these animals accounted for roughly half the meat in the diet, although more than 50 additional mammalian and other vertebrate species were identified to the late 8th and early 7th millennia.

By the beginning of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic C period, the species inventory had plummeted to about a quarter of that range in terms of diversity, and by the beginning of the 6th millennium, domesticated species (including goat, pig, cattle, and possibly sheep) provided more than 80 per cent of the meat protein, the professor underlined.

“It is curious, in passing, that domestic dogs have been claimed for Epipaleolithic sites in the Near East, dating as early as the 12th millennium, although no examples purported to be domesticated dogs have appeared in any known Neolithic site in the Near East,” Rollefson said, adding that a canid mandible with severe dental crowding was recovered from a late MPPNB/early LPPNB context at Ain Ghazal in 1988, and all indications suggest a domesticated status for this animal.

Regarding plant diet, during different excavation seasons, the samples taken differ systematically.

“The MPPNB suite of plant remains is relatively rich, with the characteristic combination of domesticated wheat, barley, peas, lentils and chickpeas, along with contributions of other resources such as figs, almonds, pistachios and a variety of ‘weeds’, some of which may have had specific uses among the residents at Ain Ghazal,” the archaeologist stressed, adding that from the LPPNB the abundant charred materials, on the basis of cursory field examination, indicate a wealth of cereals and pulses.

The situation for the PPNC and Yarmoukian periods is disappointing, however, since identifiable plant remains were extremely rare in the float samples. Charcoal, which occurred in only minute scattered particles, shows an increase of Tamarix representation, and it is clear that animal dung was being used as fuel by the middle of the PPNC phase.

The chipped stone tools were found in a big number, over 100 000 samples. All of the collections from the seasons have been sorted into debitage and tool classes, Rolleson said.

Related Articles

AMMAN — A well-known Neolithic site of Ain Ghazal is home to around half a million animal bone remains, although only a small fraction

AMMAN — During the filed season in 1996 at Ain Ghazal on the north-eastern outskirts of Amman, the archaeological team discovered a rectangu

AMMAN — Ain Ghazal (Spring of the Gazelles), near Marka in the capital, was “the Manhattan of the Neolithic period”, according to an anthrop