You are here

Italian expert ‘transforms Al Wuayra site into archaeological laboratory’

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Dec 27,2017 - Last updated at Dec 27,2017

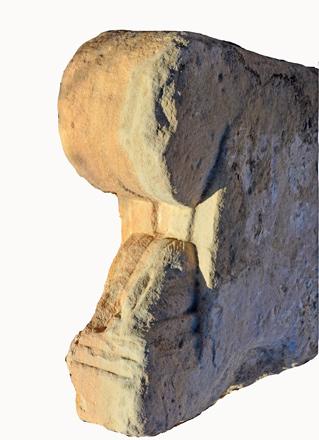

Al Wuayra site with the remains of the fortress on the hilltop (Photo courtesy of Andrea Vanni-Desideri)

AMMAN — From an archaeological and historical point of view, two features are the most important for the site: its isolation and its long-lasting human frequentation, noted Professor Andrea Vanni-Desideri, who teaches History of Settlements and Dwelling Systems at the Post-Graduate School for Archaeological Heritage at the University of Florence.

"Actually Al Wuayra site [an isolated area in Petra] works as an island: everything necessary for common use had to be brought to Al Wuayra from outside, the Italian scholar said. “ It means that whatever you find on the site has been purposely brought there through the only possible access crossing the Wadi Al Wuayra," he stressed.

On the contrary, the subtraction of materials is due, mostly if not completely, to natural factors such as land sliding, collapses and earthquakes, he continued.

“In other words, the site is a kind of closed universe of information and consequently of high archaeological significance,” Vanni-Desideri emphasised. "I think its protection should be one of the challenges in the future.”

Concerning the second factor, the nearly uninterrupted use of the site, spanning from Antiquity up to late Islamic time, it means that it was chosen because of its isolation, reputed as useful to different needs throughout its history, the scholar explained, adding that the use of the site has changed from time to time but always exploiting its isolation.

It is a kind of site very difficult to investigate because of its physical conformation, the archaeologist said, adding that the activity of the mission also pointed out that sondages ( test pit to examine the stratigraphy ), if not carefully managed, can perturb the natural equilibrium of the site.

“The managing of waste materials produced by archaeological excavations is very problematic and it needs a more acceptable behaviour in term of ‘ecology’, in order not to affect the landscape,” Vanni-Desideri highlighted.

“On the other hand, organising storage areas for such materials on the site is not feasible without blocking areas of possible archaeological interest. From my point of view it is also a question of respect of the country in which we are working,” he stressed.

Noting that he always tries as much as possible not to leave to the local population the burden of additional problems, such as cleaning or restoring the landscape.

Due to these reasons since 2011 Vanni-Desideri has applied a new methodology of research to the study of Al Wuayra in order to avoid deep sondages as much as possible, and since then the site has turned into a real laboratory to test more updated methodology of research.

“We started applying the methods of ‘light archaeology’, since decades fruitfully used in Italy by mediaeval archaeologists of the University of Florence. Basically such method consists in a combined chrono-stratigraphic and typological reading of the quantity of positive and negative data available on the surface of the soils or in the still standing building,” the professor theorised and elaborated with his colleague Guido Vannini, director of the mission with whom the Mediaeval Petra Archaeological Mission started in 1986.

Eventual excavations are then postponed to the tuning up of precise scientific questions, he stated.

“During the Late Antique phase all the features of the isolated site were accentuated,” the archaeologist said, adding that “the original connection between the pierced rock access was cut out for a better control of the entrance”.

The original dome like shape of the rock was consequently modified in order to instal a drawbridge, Vanni-Desideri continued, noting that the southern and northern ditches, altogether with the western glacis, up until now assigned to the crusaders, are a "late antique realisation".

“In addition it is during this phase that they start to bring to the site the previously absent limestone blocks as a new building material. Rough and huge blocks of this material were used for the building up of a curtain wall, while the more compact nummulithic limestone was used for the architectural elements of unknown monuments,” Vanni-Desideri said.

Moreover, the recent discovery of a particular type of water device, unknown up until now in the area of Petra, and the identification of a rock cut chapel at Al Wuayra, could be important keys for the interpretation of a third controversial phase of the site and for the progressing of the research, the professor explained.

Despite a direct participation in 30-year -old project, Vanni-Desideri is still "eager" to continue: "As you can see, 30 years of research at Al Wuayra didn’t exhausted its archaeological potential.”

The next research, which will develop during the coming period years in collaboration with the Department of Antiquities and the Petra Archaeological Park, will face the major interpretation problems, above all the pre-Crusader phases, Vanni-Desideri highlighted.

Related Articles

For the past decades, the University of Florence has been very active in Jordan, and its project Mediaeval Petra: Archaeology of the Crusade

AMMAN — The crusader castle Al Wu'ayra at Petra once was an early mediaeval chapel and even had a “hydraulic cableway” for transporting mate

AMMAN — During Baldwin I (1100-118), Crusaders built a fortress Al Wu’ayra inside Petra and the stronghold was part of the same network of c