You are here

Imports imperil Jordanian makers of handcrafted shoes

By AFP - Nov 22,2021 - Last updated at Nov 23,2021

Jamil Al Kopti, 90, the oldest shoemaker in Amman speaks at his workshop in Jordan’s capital on November 2, 2021 (AFP photo by Khalil Mazraawi)

By Kamal Taha

Agence France-Presse

AMMAN — He was once dubbed the “King of Shoes”, but after decades of fashioning footwear for kings, queens and presidents, 90-year-old Jamil Kopti fears cheap imports are killing off his craft.

“We started losing customers one after another, and we kept losing stores until we closed down three shops,” said Kopti, believed to be Jordan’s oldest maker of handcrafted shoes.

“In the past five years, our profession began to decline dramatically in face of imported foreign shoes that flooded the market,” he sighed, surveying his once prosperous workshop.

Now he has just five workers, a far cry from the 42 staff he used to employ.

And around the workshop in the popular Al Jofeh district of Amman, hundreds of moulds lie gathering dust.

After entering the trade in 1949 at just 18, Kopti attended shoe fairs every year in Bologna and Paris.

In 1961, at a show at the University of Jordan, he met His Majesty the late King Hussein and gifted him four pairs of handmade shoes.

King Hussein became an instant fan, particularly of black, formal shoes, and “after that, and for 35 years, I made the King’s shoes”.

“He loved classic shoes,” said Kopti, proudly showing off two old photos on his phone of him and the late monarch.

He was awarded Jordan’s Independence Medal and was a frequent palace guest on special occasions.

‘Made in Amman’

And Kopti’s fame spread.

In 1964, the monarch visited France where he met then president Charles de Gaulle.

“All the time during the meeting ... he had his eyes on my shoes and when he asked me where I got them from I told him ‘They were made in Amman’,” the King told Kopti.

“King Hussein asked me to make two pairs of shoes for de Gaulle,” said Kopti, adding “his shoe size was very big”.

According to the country’s Shoe Manufacturers Association, there used to be over 250 shoe workshops and factories in Jordan, employing about 5,000 people.

Today “we have around 100 workshops and less than 500 workers”, said Naser Theyabat, head of the association.

During his long career, Kopti has made shoes for His Majesty King Abdullah and most of Jordan’s princes and princesses, as well as top politicians and military officers.

Using imported leather from France, Italy, and Germany, his workshop once made 200 pairs of shoes a day.

Nowadays it is more like 10 pairs, forcing him to turn to medical shoes and children’s footwear.

But Kopti believes his loyal customers will help him survive, pointing to one client he has served for 50 years.

Handmade leather shoemakers had a “golden age” in the 1980s and 1990s, recalls Theyabat.

However with time, imports have increased.

Textile, Readymade Clothes and Footwear Syndicate head Sultan Allan said that before the COVID-19 pandemic Jordan imported about JD44 million ($62 million) worth of shoes annually.

These figures are likely to decrease due to the repercussions of the epidemic.

“This craft is on the verge of extinction,” said Theyabat, lamenting that Jordanian shoemakers received little support.

“On the contrary, there was a policy to flood the market with Chinese-made shoes.”

‘Profits too low’

In the Marina workshop in an old building of the Ashrafiyeh district, three shoemakers were sewing on soles, adding heels, and trimming off leather, watched by owner Zouhair Shiah.

“The terrible decline started in 2015 when the market was flooded with Chinese, Vietnamese, Syrian and Egyptian-made shoes,” the 71-year-old told AFP.

“I had 20 workers and I am left with three. We used to make 60 to 70 pairs of shoes a day compared with less than 12 today.”

Holding up a shoe, he pointed out it was “strong and durable” and said the pair cost JD20 ($28). “Our profit is very low.”

Shiah is hoping for government support to “reduce taxes ... because we have debts that we cannot pay”.

Bent over a machine cutting leather, white-haired Youssef Abu Sarita recalled: “I started doing this 50 years ago. I love this job and know nothing else.

“What is happening to us is sad. Most of the workshops closed and their workers have left,” he said.

“I am sure that we will face the same fate, but I do not know when.”

Related Articles

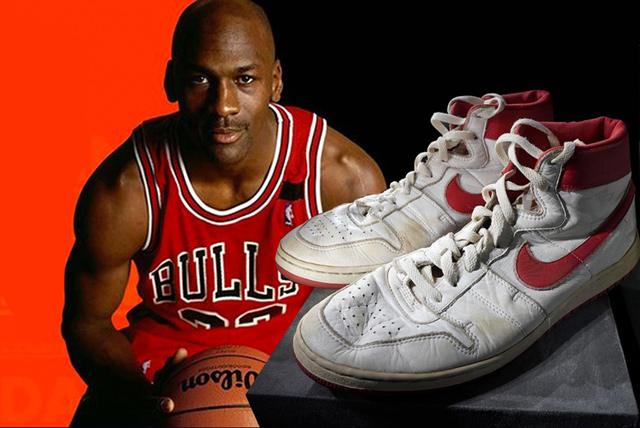

NEW YORK — A pair of sneakers worn by NBA superstar Michael Jordan early in his career sold for nearly $1.5 million on Sunday, setting a rec

LONDON — For centuries, women and sometimes men have squeezed their feet into tiny shoes or balanced on towering heels to feel sexy, empower

AMMAN — Jordan’s top all terrain drivers face tough competition from across the border once again this weekend when the second round of the