You are here

Echoes from Wadi Rum desert: Delving into Alameleh’s ancient petroglyphs

By Sophie Constantin - Feb 18,2024 - Last updated at Feb 18,2024

Camels depicted northward in the Alameleh area (Photos by Sophie Constantin)

AMMAN — The 12,000 years of human occupation in the Arabian Peninsula are illustrated through the diverse markings left by various civilisations.

Among these, the Wadi Rum desert, standing as a touristic treasure of Jordan, holds a particularly unique collection of ancient petroglyphs.

A petroglyph refers to an image formed by the removal of portions of a rock’s surface through methods such as incising, pecking, carving or abrasion using tools like a stone chisel.

The ones in Wadi Rum, mostly crafted on cliff surfaces, big rocks and boulders, have been recorded as numbering 25,000 and registered in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

The various petroglyphs depict humans, animals and symbols: Most of the human figures are holding bows and arrows, the animal figures include camels, ibex and horses, and the symbolic figures are mostly lines and circles.

In the area of Alameleh, situated near the desert oasis village of At Diseh and nestled alongside the cliffs where the valley opens in all directions, 2000 years old Thamudic inscriptions were discovered.

They depict a large number of camels travelling northward, a scene that could be attributed to the strategic location providing a clear view of desert access to the South.

Notably, some Bedouin tour guides claim that the camels are oriented towards Petra, as a symbolic way to indicate the direction of the Nabataeans’ capital city. “We cannot assume that”, clarified Firas Bqain, researcher at the Council for British Research in the Levant. “It may also be depicted by imitation: A first person drew a camel in this direction, and other artists followed his lead.” Alameleh showcases impressive large-scale depictions, including camel trains, hunting scenes, herding activities, alongside a diverse collection of texts and inscriptions in multiple styles.

These artefacts not only reflect the relatively high literacy rate among Thamudic people but also offer an interesting visualisation of the region’s technical evolutions (i.e., moving from spears, bows and arrows to swords to firearms and rifles). The camels are carved into the exposed rock face at the foot of sandstone cliffs and cover approximately 6 square metres: The largest individual inscription is a camel, measuring around one metre.

Each camel is accompanied by a Thamudic script, used for identification of ownership. The Bedouin tribes were proud of their camels, as they were their most valued possession and were widely depicted in their engravings. At the base of numerous sandstone cliffs in the area, a much harder granite base provides the ideal material for chiselling the softer sandstone and creating 2D figures. All the camels are oriented northward, with those bearing riders trailing behind, leading to a conclusion that it depicts a camel caravan.

However, evidence suggests that these inscriptions were made by various different artists made over time.

The variations in Thamudic scripts further support this notion, leading experts to conclude that they are not the work of a single tribe. Instead, these inscriptions are believed to be instructions or messages left by people for one another, providing directions or updates on recent visitors in the area.

The existence of these engravings proves a rich occupational history in this harsh desert, as well as they provide an insight into the development of human thought by showing patterns of pastoral, agricultural and urban human activity.

Additionally, the content of these engravings provides valuable climatological information: Scenes of large camel trains and hunting prey no longer found in the region, as well as domesticated livestock that the current climate cannot sustain.

The rock imagery scattered throughout the area offers glimpses into what ancient life may have been like. Four different types of scripts were found: Thamudic, Nabataean, Islamic and Arabic. “Islamic scripts may be Kufic inscriptions or anything related to religious sayings and quotes from the Koran” Bqain said, adding that “Kufic inscriptions are found mostly after Islam, around the 7th- 8th centuries, and we call it Kufic because of their similar calligraphic writing style”.

“Thamudic and Nabataean are both Semitic languages, both similar to Classical Arabic,” Bqain explained.

“However, their characters differ. While the Nabataean language is grammatically closer to Aramaic and other North Arabian languages, the Thamudic aligns more closely with Arabic, meaning that we refer to Classical Arabic when we translate it.

The Thamudic letters bears resemblance to Safaitic [found across vast areas from southern Syria to Yemen].”

Related Articles

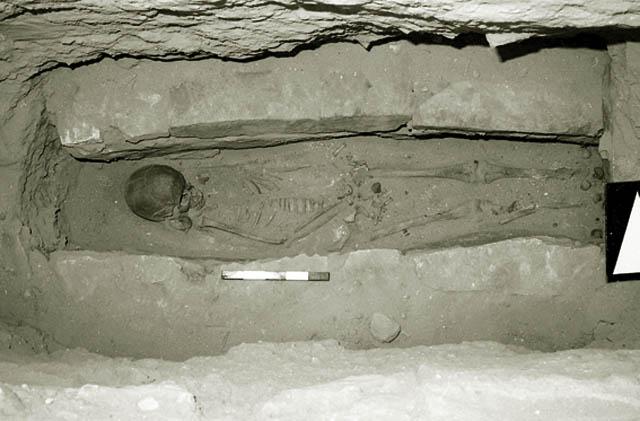

AMMAN – The late Australian scholar from The University of Sydney, William Jobling, meticulously studied inscriptions in the Wadi Rum back i

AMMAN — The ancient Nabataean site of Hawara has been the focus of the research of two Canadian scholars. The rock-cut tombs in the nec

AMMAN — William Jobling, the late professor at the University of Sydney, was the head of the Aqaba-Maan Archaeological and Epigraphic Survey