You are here

Classical funerary depictions: Unveiling traditions of Roman Jordan

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Apr 21,2024 - Last updated at Apr 21,2024

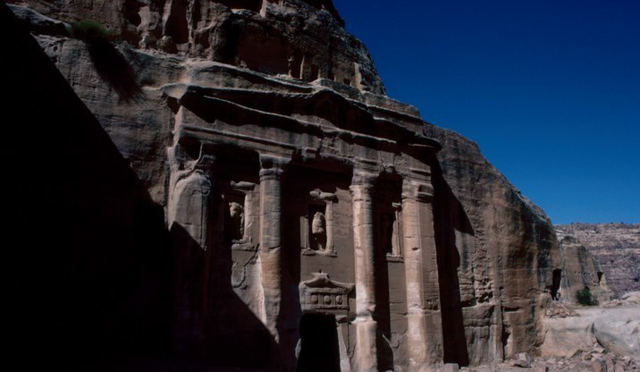

Bust of Hermes and Bust of Athena in Petra (Photo courtesy of ACOR)

AMMAN — Busts are among the most widespread forms of funerary depictions of a deceased individuals. During his research on funerary sites, Bilal Annan, from the University of Paris, found around 130 busts from the Roman period in Jordan.

Busts were relatively cheap and easier to prepare than other artistic forms, unlike the full-figure statue, for example.

“Most of the busts found in the necropoleis of Jordan are rather rudimentary: the bust of Theodros, from Abila [Quwayliba], dated to the 2nd or 3rd centuries AD, is characterised by an oval-shaped head with a flat face, slanting eyebrows, closed eyelids, thin nose, narrow lips and monstrously widened chin, resting on a massive cylindrical neck and a block-like torso lacking any indication of anatomical features,” Annan said, adding that one can hardly believe that the author of such a portrait sought to reproduce the appearance of a particular individual, or to individualise the image through physiognomic characteristics (relating a physical appearance to a mental state of an individual), yet, the patron must have judged it sufficiently expressive as to have it stand in lieu of the deceased, whose identity is given by the brief epitaph carved on the torso: “Be brave, Theodoros”.

A second bust —contemporaneous, uninscribed, and of the same provenance —features an abstract bust with rather bloated forms, deep-set eyes, and arms that are merely delineated through shallow carving under the armpits: the only hint at the deceased’s gender is given by faintly incised breast Limestone contours (which might have been added at a later stage of its existence).

“Such ‘crude’ portraits are attested all over the Roman Empire, and strikingly similar items have been unearthed, for instance, in Baelo Claudia in Hispania and in Kenchreai, the eastern port of Corinth,” said Annan.

The unflattering aspect of these crude portraits should not, however, obscure the fact that this phenomenon was essentially confined to the social circles of the most affluent citizens of the Decapolis, since these portraits were most often displayed in hypogea (underground chamber) and monumental tombs, the very construction of which represented a substantial investment.

Furthermore, the bust form was sufficient —indeed, most effective— in its commemorative function, in that it reduced the deceased’s identity to two elementary components: the name (epitaph) and the face (image) —Lat. Nomen and vultus; Gk. onoma and prosōpon— which were, for the Classical mind, the two ultimate seats of individuality, Annan underlined.

Wall painting represents another form of funerary representation and allows people to gain a glimpse of a fleeting —indeed, long lost— reality, in which the ancient viewer’s senses must have revelled, which is that of a colourful antiquity.

“While in Sidon on the Phoenician coast, we know of some Late Hellenistic or Early Imperial painted stelai, no such documents have yet been found, to my knowledge, in Jordan, where painted funerary portraits most often adorn walls on the edges of loculi [chamber] and arcosolia within funerary enclosures. One particular archaeological site, Abila [Quwayliba] has provided us with a wealth of such documentation,” Annan highlighted.

Remarkable among those Abilene portraits is the bust, painted above a loculus

in the eponymous tomb H3, of an elderly man shown above an elaborate garland of flowers and beneath two festoons of red, yellow, and green floral motifs, and set in a floral frame against an ochre background, he said.

The old man is dressed in a white tunic and his grey hair, moustache and beard, his receding hairline and wrinkled forehead attest to his old age.

Another partially preserved painting, in the tomb H60, shows in a floral medallion a woman whose face, with its greying hair and sagging flesh, seems to exhibit features of old age.

“Old age is a notable feature in a body of portraits, whether in the Near East or the wider Roman Empire, as it is a frequent subject of ridicule in Classical literature and was only reluctantly expressed in portraiture, despite the wisdom and moral authority such traits would have conventionally conferred upon the depicted individual,” Annan said.

Related Articles

AMMAN — A funerary portrait serves as the lasting image through which the deceased hoped to be remembered by posterity for all eternit

AMMAN — A sarcophagus (plural “sarcophagi” or “sarcophaguses”) is a coffin commonly carved in stone and displayed above ground. During

Al Qunayyah is a site located approximately 10 km southeast of Jerash, and its ancient name is still unknown.