You are here

Beyond kingdoms: Unravelling political complexity in Levantine Bronze Age

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Apr 23,2024 - Last updated at Apr 23,2024

Khirbet Faynan in southern Jordan. Wadi Faynan was a significant copper centre in the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age (Photo courtesy of ACOR)

AMMAN – The Bronze Age in Greece and Levant was a period marked by great kings and local ”small” kings. The imperial centres in Egypt, Asia Minor and Mesopotamia exercised political, military and economic control over statelets located between them. During the time span of hundreds of years, same statelets would become vassals of one major power and after different political changes, they would switch its allegiance towards the other.

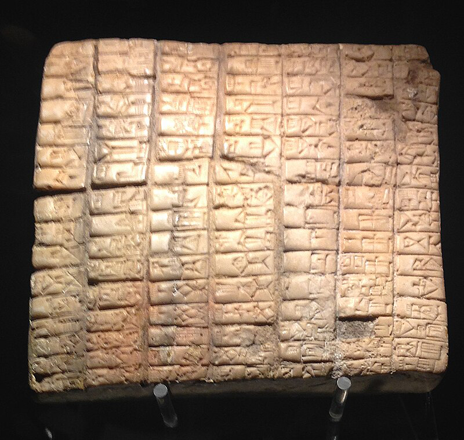

The archives in Ugarit and Alalakh (located 20 kilometres northeast of modern Antakia in Turkey) as well as Egyptian and Hittite correspondence, and other relevant texts, attest to that.

“Because of the historical imperative, which drove much earlier archaeology in the region, excavation has traditionally tended to focus on sites thought to be important, named or potentially named in the textual record, and above all likely to provide further archives,” said Susan Sherratt, a British archaeologist, adding that as a result, scholars know more about the material remains, official personnel and political interrelationships of top-level centres in hierarchical structures than they do about more humble settlements, which are generally textless and anonymous.

This notion changed in the recent decades and archaeological teams paid more attention to smaller sites.

While these may not necessarily tell us everything we might like to know about the political relationships between major centres and their “hinterlands”, they do help to add a necessary degree of complexity to the picture and remove some of earlier more simplistic assumptions and text-derived generalisations.

“In particular, they have, with the help of insights imported from such disciplines as political sociology or human geography, increased our appreciation of the probable diversity of political organisation, which characterised the Late Bronze Levant as a whole,” Sherratt continued, adding that in Cyprus, where ”we lack the assistance of readable indigenous texts and where external references to Alashiyahave the effect of raising rather than answering questions, the problem of political organisation in the Late Bronze is still very much disputed.”

“On the face of it, given the naturally centrifugal geography of the island with its series of river valleys running down from the copper-bearing Troodos Massif and looking outwards towards the sea on the south, west and east, and its narrow coastal strip backed by the Kyrenia Range in the north, it seems unlikely that the whole of Cyprus was ever politically controlled by any one centre, any more than it was in the later Archaic and Classical periods, when we can read the Cypriot syllabic inscription,” Sherratt maintained.

Moreover, in the Late Bronze Age, Enkomi would become a dominant site on the island.

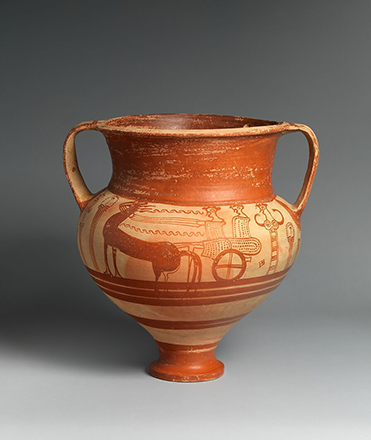

That is not to say, however, that, especially perhaps in the early Late Bronze Age, a centre like Enkomi did not have a particularly dominant role in the island’s political and economic relationships with the Levant before, perhaps, other centres in the south of the island got in on the act, forming external relationships on their own account. “Here, surveys combined with excavations in various parts of the southern section of the island have indicated the existence of different types of apparently specialised sites, ranging from farming villages, copper-mining and smelting communities, and probably seasonal pottery-production locations to what appear to be administrative centres dedicated to the processing of agricultural products and coastal cities engaged in trading and manufacture, with urban sanctuaries, city walls, and [in some cases] a regular grid layout,” Sherratt underlined.

Cyprus and Wadi Faynan were two significant hubs for copper smelting and export, and that trade has every appearance of being a complex and highly dynamic pattern of political and economic interaction. “It is perhaps something of a cliché that the ancient Levant, throughout much of its history, lay at the centre of the world. It formed a corridor and junction between north and south, east and west; and the regions [based on modern political boundaries],” the scholar said, adding that in the Late Bronze Age, it also acted as an active crucible in which ideas, technologies, materials, goods and ideologies, some of them deriving originally from surrounding areas, were melted together to produce an eclectic cultural and ideological alloy with its own distinctive character, in which the Levant’s central position in a wider “civilised” world.

Related Articles

AMMAN — During the Late Bronze Age, economic interconnectedness characterised relations between Egyptian dynasties, Hittite state and

AMMAN — During the Bronze Age, Cyprus played a role of cultural and economic hub, as well as a bridge between the Levant and southern Europe

AMMAN — Ebla tablets found in 1975 by the Italian archaeologist Paolo Matthiae represent a collection of 1,800 clay tablets, 4,700 fra