You are here

‘Rewriting our history... and the future’

By Sally Bland - Oct 15,2017 - Last updated at Oct 15,2017

On the Arab-Jew, Palestine, and Other Displacements

Ella Shohat

London: Pluto Press, 2017

Pp. 464

This book contains a selection of the writings of Ella Shohat, Professor of Cultural Studies and Middle East Studies at New York University: “texts that critique the intellectual and methodological ‘separation fence’ that has segregated struggles, stories, and possibilities”. (p. 18)

While her research springs from her own background, these texts, written over a period of 35 years, show how she developed and expanded her ideas on displacement and the political/cultural silencing of marginalised populations into an inclusive global perspective.

Born into an Iraqi-Jewish family that was forcibly transplanted to Israel in the early 1950s, Shohat’s original focus was on the precarious position of Arab Jews (Mizrahim) in the new state. She chronicles the abuses they suffered, including the kidnapping of their babies to be adopted by Ashkenazim (European Jews), a scandal that is finally being investigated by the Israeli government over half a century later. Overall, the Mizrahim were considered backward or worse by the Ashkenazi leadership, and Shohat zooms in on their cultural suppression. In fact, they had no voice, no real place in the official Israeli narrative, for they could not be both Jews and Arabs, the latter being designated as “the enemy”. “If Palestinians paid the price of Europe’s industrialised slaughter of Jews, Arab Jews woke up to a new world order that could not accommodate their simultaneous Jewishness and Arabness.” (p. 3)

Refreshingly, Shohat does not engage in competition about who has suffered most; nor does she equate the displacement of Arab Jews with the Palestinians’ dispossession, but contends that the two displacements are connected. “What is desperately needed for critical scholars is a de-Zionised decoding of the peculiar history of the Mizrahim, one closely articulated with Palestinian history.” (p. 121)

Thus, the status of Mizrahi Jews is not only an internal Israeli matter, but should be part of seeking a solution to the conflict. “Like the shared plural space that was Palestine, the Arab-Jew is a reminder/remainder of the plurality in the Arab world more generally. Both ‘Palestine’ and ‘the Arab-Jew’ in this sense are not only tropes of loss and mourning but also figures of inclusivity… the concepts evoke a memory of a shared past while also pointing to a likely future of re/conciliation.” (p. 10)

In 1981, when Shohat relocated from Israel to the US, she felt more at home in New York, which was filled with multicultural persons like herself, and she became part of the progressive academic community there. Shohat’s perspective in many ways overlaps with that of Edward Said, and she pays tribute to his great contributions to scholarship on the Middle East with his seminal work, “Orientalism”. It is not by accident that the title of her groundbreaking essay, “Sephardim in Israel: Zionism from the Standpoint of its Jewish Victims” (1988), was patterned on the title of one of Said’s early expositions of the Palestinian cause. Like for Said, breaking down false dualities is not only an academic exercise for her: “It is about rewriting our history and writing a new pathway for the future”. (p. 424)

Well before multiculturalism and postcolonialism were common approaches in western academia, Shohat established her reputation as a cultural critic — and drew much criticism in Israel — with her book, “Israeli Cinema: East/West and the Politics of Representation” (1989), which expanded her critique of Zionism to include its (mis)representation not only of Arab Jews, but of Palestine and the Palestinians. Besides introducing Shohat’s ideas, the book serves as a review of milestones in the progressive organising and cultural politics in which she participated. In 1989, she attended the Toledo meeting between Sephardi Mizrahi Jews and PLO-linked Palestinians, including Mahmoud Darwish, later writing: “we insisted that a comprehensive peace would mean more than settling political borders, and would require the erasure of the artificial East/West cultural borders between Israel and Palestine, and thus the remapping of national and ethnic-racial identities…” (p. 177)

In 1996, Shohat was among the women who split from the Israeli Women’s Movement to form the Mizrahi Feminist Forum to go beyond “the simplistic Euro-Israeli analysis which reduces everything into a dichotomy of man-versus-woman”. (p. 98) Instead, they aspired to link Mizrahi, Palestinian and feminist concerns, and situate themselves in a multicultural struggle against racism and colonialism.

Shohat also writes about Mordechai Vanunu, Palestinian and Egyptian cinema, how the media presented the US invasion of Iraq, the continuing relevance of Franz Fanon and many other topics. In all her writing, there is constant examination of concepts one often takes for granted such as nationalism, universalism and humanism. Shohat cherishes hybrid identities and cultural differences, but in a way that encourages the discovery of new-found commonalities. Reading this book will sharpen one’s critical skills, helping to sort out the truth in the avalanche of media to which all are exposed in today’s world.

Always on the cutting edge, Shohat’s ideas are doubly relevant today as efforts to find a democratic, peaceful solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict are at an all-time low, and massive population dislocations have reached an all-time high.

Related Articles

It is very life-affirming to see a book of such beauty about Iraq, but this is not art for art’s sake or an attempt to avoid ugly reality.

While the title of this book suggests that it covers a single topic, nothing could be farther from the truth.

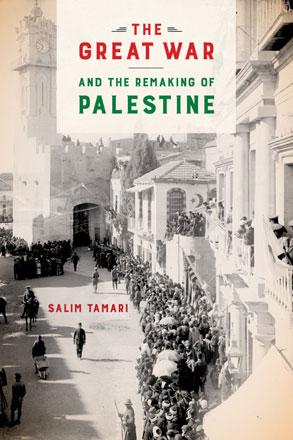

The Great War and the Remaking of PalestineSalim TamariUS: University of California Press, 2017Pp.