You are here

Resurrecting the role of Latife Hanim

By Sally Bland - Jun 03,2019 - Last updated at Jun 03,2019

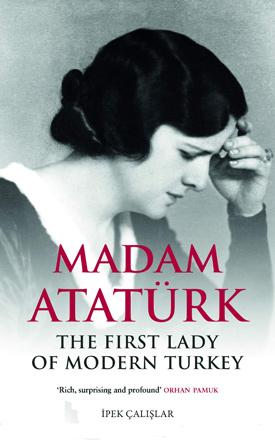

Madam Ataturk: The First Lady of Modern Turkey

Ipek Calislar

Translated from Turkish by Feyza Howell

London: Saqi Books, 2019

Pp. 364

A few decades ago, a new trend in literature emerged to tell the stories of women who were known mainly due to their relationship to famous men. One such book, a novel, was “Ahab’s Wife” (1999) imagining the woman who waited on shore while Captain Ahab pursued the legendary white whale, Moby Dick. Another example, also a novel but adhering to known facts, was “The Paris Wife” (2011) about Hadley Richardson, Ernest Hemingway’s first wife. While these books were more or less fictionalised accounts, “Madam Ataturk” is a true story and falls in the genre of biography.

Even in her own country, little meaningful has been written about Latife Hanim, who at the age of 24 married Mustafa Kemal, the founder of modern Turkey, known as Ataturk. Hugely popular among those who saw the establishment of the Turkish Republic as the path to modernity and improvement in women’s status, Latife was largely ignored and even defiled after he divorced her a scant two and a half years later, despite her having been highly educated and active in public affairs. Turkish journalist Ipek Calislar took this lacuna as a challenge: “The moment I discovered she had demanded Ataturk change the law to enable her to stand for parliament, I knew I had found the woman whose biography beckoned”. (p. 7)

The book stands as evidence that Calislar threw herself wholeheartedly into the project, researching in a myriad of sources — books, newspapers and magazines of the times, Turkish, European and American. She also interviewed surviving relatives and others who had known Latife and Ataturk personally. The result is an engaging account of their life together in which the personal and political are closely intertwined. There are many issues on which different sources give conflicting accounts, from the question of whether theirs was a love marriage or not, to the reasons for their separation and Latife’s life post-divorce. Calislar presents the many viewpoints and then states her own opinions, making the book a shining example of how history can and should be written, both exploring new interpretations of the past and drawing well-grounded conclusions.

The author is adept at painting a scene, so that the reader feels privy to pivotal events as well as small, sometimes amusing, incidents in Latife’s and Ataturk’s life that reveal their respective personalities and motivations. What is less clear is the rendering of the historical events of the time. If one is not well-versed in the first years of the Turkish Republic, things can be a little confusing, but the main point of the book, to reinstate Latife’s important political role, is abundantly clear. While she ran the household smoothly, even elegantly, she was most distinguished as Ataturk’s companion, his secretary, and someone he could discuss ideas with, especially what needed to be done to advance the liberation of women. Moreover, with her fluency in English, French, German, Farsi and Arabic, and her knowledge of European society gained while studying in London and Paris, Latife was a great assert to the new Turkey’s foreign relations, interacting gracefully with ambassadors and sought after by the foreign press.

One also gets a lovely impression of Izmir, Latife’s home city, where her father, Muammer Ussakizade, was the leading businessman and provided an advanced education for all six of his children, girls as well as boys. According to the author, “The family faced west, but preserved eastern values.” (p. 27)

Latife and Ataturk discussed and agreed on many issues, such as that education should be secular, the veil should be discarded and unilateral divorce and polygamy abolished. The interesting thing is that these opinions on her part predated her 1923 marriage to Ataturk and even her time studying in Europe (after 1919); as the author points out, “By 1916 Latife was reading all she could get her hands on regarding women’s issues…” (p. 33)

Calislar also paints a sobering picture of the prevailing situation which Latife and Ataturk wanted to change: “Seclusion [of women] still dominated the social life of the nation. Social life, especially in Ankara, excluded women entirely… “(p. 187)

In this context, Latife appearing unveiled at a public event alongside her husband rippled throughout Turkish society. Calislar does not claim that Latife was the founder or leader of the Turkish women’s movement but explains how she was able to exert much influence by virtue of being Ataturk’s wife and her own persistent personality. “I consider it a great loss to the women’s movement that Latife’s pioneering role at the time has been forgotten, and worse, deliberately obliterated”. (p. 197)

Ironically, “Latife was the iconic woman who had made women visible, although she herself lived the rest of her life as the invisible woman”. (p. 313)

This book is a well-researched and well-written effort to make her visible again.

Related Articles

Fahrelnissa and I: A MemoirJanset Berkok ShamiIstanbul: Cinius Publishing House, 2016Pp.

A Strangeness in My MindOrhan PamukTranslated by Ekin OklapNew York/Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015Pp.