You are here

Paying tribute to the legacy of Muslims in Al Andalus

By Rand Dalgamouni - Nov 20,2015 - Last updated at Nov 20,2015

Work by Tariq Dajani on display at Jacaranda Images until November 26 (Photo courtesy of Jacaranda Images)

AMMAN — In his latest exhibition “Kitab Al Filaha” at Jacaranda Images, artist Tariq Dajani pays an evocative tribute to the legacy of Muslims in Al Andalus.

His meticulously created photography artworks hark back to a time when Muslims populated southern Spain’s La Alpujarra region, focusing on an aspect of Andalusian legacy that is often overlooked — their achievements in agriculture.

“There were no beautiful palaces or other splendid monuments by the Muslims in the Alpujarra. Yet their presence can be felt almost everywhere: in the names of villages… in the names of agricultural produce; and in the methods of farming and irrigation systems,” Dajani writes in his notes on the exhibition.

His photographs shed light on what Muslims left behind in farming techniques and animal husbandry, with the name of the exhibition coming from an authoritative encyclopaedia on agriculture by 12th century Muslim scholar Ibn Al Awwam Al Ishbili of Al Andalus.

Ruins of old farmhouses, remains of cattle raised by farmers in the past, olive trees planted centuries ago and the fruits and nuts borne by those trees are some of the subjects of Dajani’s pieces, where he skilfully manipulates the focus through his lens to enrich each photo.

In keeping with the spirit of the subject matter, the artist revives a photo printing technique that dates back to the 1800s in a tribute to the time and effort invested in the manual agriculture methods he seeks to highlight.

“I wanted a printing process that would be true to that notion… instead of just making digital prints, I thought it would be nice to make prints by hand,” he told The Jordan Times.

His use of the labour-intensive photogravure technique produces unique black-and-white prints with a sense of raw detail unlike that of regular digital prints.

Instead of being just another collection of photogenic images of beautiful trees and fruits, Dajani’s prints have a depth and degree of detail that speak of the time and effort put into creating them.

“I spent one and a half years learning how to print like that,” he said.

The method entails etching a photo onto a light-sensitive surface on a metal plate by exposure to ultraviolet sunlight.

“Oil-based inks are then pressed into the etched grooves and gently wiped. The deeper grooves retain more ink than the shallower ones, corresponding to the tonal range of the image,” according to Dajani’s notes.

The metal plate is then “placed on the bed of a traditional printing press and a damp piece of heavy-weight art paper” is positioned on top of it before both are “rolled through the press”, the artist explains.

In addition to the range and layers that each print gains from this process, having black-and-white photos also brings something to the work.

“Because they are black and white, the viewer is required to perhaps put more effort into feeling the picture and understanding… or seeing what they get out of it,” said Dajani.

The artist is also influenced by the still-life paintings of Spanish masters such as Francisco Goya and Diego Velazquez in their “staged presentation of objects”, and the use of light and shadow.

Employing similar techniques, “allowed me to present the work in a way which would isolate it from an environment and make it kind of more dramatic and theatrical,” he said.

The still nature of each piece and — paradoxically — the portrayal of life in the seeds, fruits and tree branches adds to the binaries of black and white, light and shadows.

The artist says he sought to explore this link between past and present, life and death. He was also intrigued by the use of pieces of string to position objects in these early paintings, employing it himself visibly in some of the photos and seeing it as a metaphor that links past and present.

The careful thought and effort that Dajani invests in each little aspect of every piece pushes the viewer to take similar meticulous effort to examine his work and soak in all the details.

The artist stresses that he does not want the process he used to take away “from the overall message of the work”, which sheds light on a bygone era whose legacy lives on today.

If anything, his work inspires one to examine and appreciate this forgotten past of Al Andalus better than thousands of words in history essays.

The exhibition continues through November 26.

Related Articles

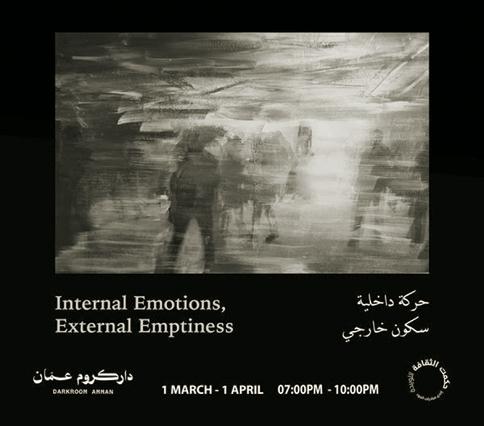

AMMAN — Focusing on local experience and talents, Darkroom Amman, a project that aims to promote analogue photography, recently launched an

AMMAN — Silence’s capacity to convey a wide range of emotions, often more successfully than words themselves, is one of the ideas explored b

AMMAN — Rana Dajani, an associate professor at the Hashemite University, has been selected by the Radcliffe Foundation for Advanced Study at