You are here

New Circassian scholarship — between homeland and diaspora

By Sally Bland - Feb 26,2018 - Last updated at Feb 26,2018

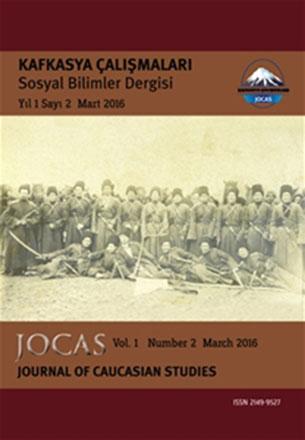

Istanbul: Journal of Caucasian Studies (JOCAS), September 2015-March 2017

The Journal of Caucasian Studies (JOCAS) is a peer-reviewed, bi-annual, international, academic journal.

It is also multilingual, including articles in English, Turkish and Russian. JOCAS gives voice to a new generation of Circassian scholars who have emerged in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse, and are assertively researching the history and culture of the Caucasus in the context of today’s globalised world. Included in the editorial board is anthropologist Seteney Shami, who grew up in Jordan, taught at Yarmouk University, and is now director of the Arab Council for Social Sciences in Beirut.

The first issue of JOCAS (Vol. 1, No. 1, September 2015) attests to the intent to cover historical as well as contemporary issues in many fields of relevance to Circassian communities at home and in the diaspora.

Lars Funch Hansen leads off with an article entitled “iCircassia: Digital Capitalism and New Transnational Identities”, contending that: “A concrete empowerment of Circassian actors through the Internet is taking place.” (p. 1)

Whereas the exile of Circassians from their homeland in 1864 wiped Circassia off the map, the recent creation of many Circassian websites and Circassians’ avid use of social media has restored their homeland to the global map. Hansen considers this on-line activity part of the Circassian revival, and poses many pertinent questions about its implications, such as how the Internet contributes to new hybrid identities, and whether it will encourage Circassians to return to their ancestral homeland or have the opposite effect.

In another article in JOCAS’s first issue, Sufian Zhemukhov and Sener Akturk address the future of the Circassian language by analysing Russia’s language policy over the years. They begin by noting that “although the Soviet Union was originally the most ardent supporter of multiethnic, multiculturalist, affirmative action policies when it was founded in the 1920s, the political leadership in Moscow gradually shifted towards assimilationist state policies already during the Soviet period but decisively after the collapse of the Soviet Union”. (p. 42)

The authors innumerate the many obstacles to reviving the Circassian language erected by said state policy, and connect language to other issues such as nationalism, education and immigration possibilities. They conclude, “Circassians and other non-Russian ethnic groups struggle with an ineffective language policy and an education system that puts their languages on the brink of extinction.” (p. 65)

A third article in the same issue by Yahya Khoon focuses on Prince Sefer Bey Zanuko who led the Circassian resistance to Russia’s conquest of the Northwest Caucasus in the early 19th century, but has received less attention in Western and Soviet research than the leaders of the resistance in the Northeast Caucasus. Though this article is purely historical, one notices a parallel to current reality, though Khoon does not mention it: Prince Zanuko’s main rival for leadership was Muhammad Amin, an Islamist, who was bolstered by ties to Imam Shamil, the famous leader of the militant Sufi movement, presaging by over a century the Islamist challenge to nationalist movements and regimes throughout the Middle East.

This biographical account is one of several in the journal’s first issues. Other important persons covered are Hadji Murat, a deputy of Imam Shamil; Muhammed Zahid Shamil, Imam Shamil’s grandson; and General Musa Kundukhov, who organised the resettlement of approximately five thousand Chechen, Ossetian and Circassian families in Ottoman territory.

In the March 2017 issue (Vol. 2, No. 4), there is an interesting article on the return of the Adyge and Abkhaz living in Turkey to their ancestral homeland in the Caucasus—something that had only been a dream until the collapse of the Soviet Union. Many visited, but some decided not to settle down in view of the difficult conditions prevailing in their homeland. Others, “with a decision to burn all the bridges, moved to the homeland for good”. The author, Jade Cemre Erciyes, concludes, “Since 1991, the ideology of return has been transformed according to the conditions of travel and communication.” (p. 2)

The topics covered in the journal’s first two years of publication are wide-ranging. History predominates with studies of the Caucasian politics of Russian Tsar Paul I; the Circassian-Polish-Hungarian Alliance in the final days of the 1848-1848 Hungarian Revolution; “Russification” in the North Caucasus; the Abkhazian migration of 1867 to the Ottoman Empire, as recorded in Russian, Ottoman and British documents; and Ottoman policies on Circassian refugees in the Danube Vilayet (today Bulgaria), as well as social projects for children, the poor and the elderly among the immigrants there.

Other articles involve culture and/or more current issues, such as mythological narratives in the folklore of the Circassian diaspora in Turkey; current and potential ethnic conflicts in the North Caucasus; the phenomenon of political alienation in the historical fate of the Circassian people; and Circassians in American newspapers. Some volumes include reviews of relevant books.

Judging from the first few issues, JOCAS will contribute not only to Caucasian studies, but to historical reassessment of aspects of Ottoman, Russian and great power politics, as well as to refugee, displacement and diaspora studies in a global context. JOCAS can be accessed online at http://dergipark.gov.tr/jocas

Related Articles

AMMAN — After the military campaigns of tsarist Russia in 1863–64, which resulted in the ethnic cleansing of Circassians and the displacemen

The Kindness of EnemiesLeila AboulelaNew York: Grove Press, 2017Pp.

AMMAN — In the middle of the 19th century, the northern Caucasus was a battlefield between the Russian and the Ottoman empires.