You are here

‘A minority under siege’

By Sally Bland - May 27,2018 - Last updated at May 27,2018

Born in Jerusalem, Born Palestinian: A Memoir

Jacob J. Nammar

US: Olive Branch Press/Interlink, 2012

Pp. 152

This book is both charming and painful to read. It is also very instructive: It dovetails with the overall Palestinian narrative of dispossession and ethnic cleansing, yet also conveys a unique experience.

Born in 1941, Jacob Nammar had almost seven years of normal, somewhat idyllic, childhood in a big, close-knit, Christian family in Baq’a, a new quarter built outside the Old City walls on the western side of Jerusalem. He begins with a beautiful account of their way of life: his mother’s delicious, fresh food; her enchanting storytelling; playing in the nearby woods; visiting friends in Battir village; trips to the communal bathhouse and occasionally to the cinema; and the exciting tales brought home by his father who travelled throughout Palestine and farther afield, driving a tourist bus.

Though neither of Nammar’s parents had a formal education, they spoke multiple languages, as did he and his siblings. Most significantly, they had well-defined cultural and spiritual values: “They emphasised the Ten Commandments and the traditional Palestinian value of respect for others, irrespective of their religion, race, or ethnicity. They taught us not to hate but to love everyone as children of God, and to believe in ‘karamah’—dignity and generosity.” (p. 18)

Telling his story in retrospect from his adopted home in the USA, where he emigrated as a young man, the amazing thing is that Nammar recounts the next phase of his life — the 1948 Nakba and its consequences — so vividly but without hate. While clearly delineating the injustices done to his family, parallel to the catastrophe inflicted on the Palestinian people as a whole, and his outrage at the ethnic cleansing that is still going on, he did not stop living by the values his parents taught him.

While in some ways the Nammar family was very typical, in other ways they were exceptional. Jacob’s mother was Armenian and a divorcee, and his father married her despite the opposition of his extended family, something which was not very common at the time.

In the foreword, Palestinian scholar Salim Tamari notes that the extended Nammar family was the only family in Jerusalem after whom a neighbourhood was named. More crucially, while most Palestinians living in the western sector of the city and its environs were expelled eastwards, Jacob’s family remained on the western side of the city, though not in their own home.

Nammar poignantly describes how he was affected by the violence that led up to the creation of Israel: an attack on his school bus as it passed the Montefiore Jewish Colony, killing two classmates; the Irgun blowing up the King David Hotel where his brother worked; the Deir Yassin and Dawayma massacres. When Zionist militias began attacking the Palestinian suburbs on the western side of the city, most of the neighbours fled. Jacob’s parents were determined to stay, but as the war came closer, opted to seek temporary refuge at the German Colony Hospital. On the way, his father and oldest brother were abducted by Zionist soldiers. When the rest of the family returned to their home about a week later, they found it looted and vandalised.

The Nammar family experienced a peculiar version of the Nakba: under a military administration law, they were forced to relocate to an unfinished, primitive apartment building in a fenced security zone which Nammar terms: “a ghetto and a large open prison camp, surrounded by eight feet of barbed wire, with armed guards preventing anyone from leaving or entering. There was no communication with the outside world… we became a minority under siege and an extension of the war. We were innocent young children, yet we had to learn to survive as individuals. We measured our ability to sustain ourselves by the way we supported each other and stayed strong as a family”. (p. 62)

Thus began a time of poverty, dependence on UNRWA rations, lack of schooling and Shin Bet harassment. After some years, Nammar’s older brother and later his father were released and reunited with the family, but his father was never the same again.

Nammar’s account of the ensuing years exemplifies how the racism inherent in Zionism precludes coexistence between Palestinians and Israelis and slams the door in the face of Palestinian success. Eventually, Jacob and his siblings were able to return to school and found various jobs to keep the family afloat, but virtually all were to lose these jobs due to discrimination. For his part, Jacob had many Jewish friends and excelled in sports, especially swimming and basketball. He was selected for the Israeli National Basketball Team and ranked the seventh best player in the country, but as preparations for the Olympics were under way, he was abruptly dropped from the team. Ironically, at games, there were those who yelled at him: “Go home!”

Nammar’s memoir is both a celebration of Jerusalem’s multiculturalism long before the term became fashionable, and an indictment of the racism and ethnic cleansing that have reversed the city’s historical legacy. Above all, it is a deeply human story of a Palestinian family who did the best they could in extremely trying circumstances.

Related Articles

OCCUPIED JERUSALEM — Israeli occupation authorities demolished a residential building in occupied East Jerusalem on Tuesday, leaving 35 peop

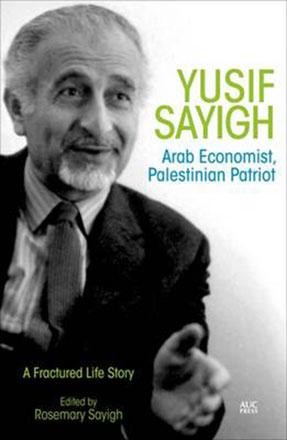

Yusif Sayigh: Arab Economist, Palestinian Patriot — A Fractured Life StoryEdited by Rosemary SayighThe American University in Cairo Press, 2

ATLIT, Israel/Beirut — Waving Palestinian flags and wearing T-shirts proclaiming Jerusalem to be "the eternal capital of Palestine", thousan