You are here

Mezzotint works light up the imagination

By Ica Wahbeh - Oct 24,2015 - Last updated at Oct 24,2015

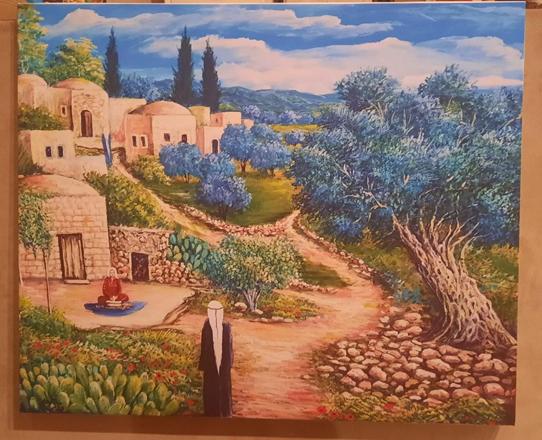

Works by Hachmi Azza in his ‘Retrospective Exhibition of Mezzotint Works’ on display at the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts until December 20 (Photo courtesy of the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts)

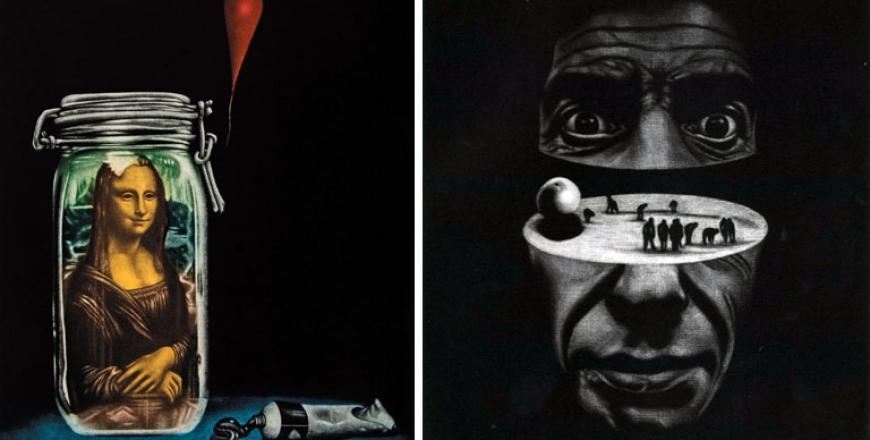

Surrealist, symbolic, in warming colours and intriguing dark-light contrast, Hachmi Azza’s “Retrospective Exhibition of Mezzotint Works”, at the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, is fascinating.

The richness and precision of detail found in the relatively small-size works might be facilitated by the technique, but the artist’s skill is indisputable.

Of Belgian nationality and living in Germany, Azza was born in 1950 in Morocco. From 1965 to 1969 he studied at L’Ecole de Beaux Arts Tetouan Morocco; between 1969 and 1972 he pursued his studies at the Academie Royale des Beaux Art and from 1972 to 1976 at L’Ecole Nationale Superieure d’Architecture et d’Art Visuel, both in Brussels.

He donates the works now on display in Jordan to the gallery, adding to the already rich collection of this prestigious institution, to the delight of art lovers.

Azza’s technique, mezzotint, is used by no other Arab artist, according to gallery director and curator of this exhibition Khalid Khreis.

The works, ranging from 1976 to 2009, are loaded with symbolism. Already often overt, it is usually reinforced by the titles given by the artist to his works.

In “The Metamorphosis”, for example, a flame-carrying butterfly sets light to rows of matches in some kind of reverse role. Over their burnt heads, two images later, hangs a moon-like sphere, most likely a cocoon from which another butterfly will emerge.

The sphere, this perfect form that is the symbol of myriad things, is constantly present, one of many other objects present in Azza’s works: shells, butterflies, fruit (predominantly cherries and apples), snails, animals, masks.

They are both highly decorative and carry “hidden” meanings the viewer is invited to find out.

Beyond the objects, feelings and insecurities are skillfully rendered by the artist in images that touch the soul.

Fragility, nostalgia, fear, emancipation, freedom… all surface against the dark background on human faces or objects in delicate or fantastic combinations.

Things, portraits and organic matter are juxtaposed or precariously balanced to make a static image a moving imagery. The “I object” series of three grotesque portraits is a progression from a one-eyed (the mythological Cyclops?) one-toothed, ambiguous face (no saying whether it is a man or a woman) to a more normal (two eyes, all teeth) screaming face that could express anguish, anger or, as the artist suggests, objection.

Poignant images depict a “handicapped” headless person whose prosthetic leg carries the head; a mirror ideally reflects the image desired by the observer; a sad figure and a donkey in a globe of light in “Interrogation” make one wonder who is interrogated and who the interrogator; yet another headless body attempts to keep balance, on a tilted chair, with a big head facing it.

They are stirring images that give food for thought, that could provoke deep searches for meanings of human acts or, simpler, be seen just as surrealist scenes allowing the unconscious to express itself.

“The Deaf” is a huge ear carrying, for an earring, a screaming head, a world upside down, a reversal of roles, yet again, an image making one wonder which refuses to hear: the ear or the mind.

“History of the Apple” is an interesting series of eight images of a green apple and its various functions or symbolism, arranged in alphabetic order (A to H).

Whether with a face reflected in it, its core rendered by a lady bug, tied in thick cord, bitten, cored, its empty skin coiled in the shape of the fruit or, sending one to the beginning of creation, a snake coiled around it, the apple serves as an aesthetic object or food for snails or grasshoppers, but could also, symbolically, be the apple of discord and the reason for the fall from Eden, an innocuous fruit, but also the reason for the primordial sin.

Still life with fruit, vases, pens, pins, lines, angels, masks, crustaceans, grasshoppers make compositions that keep peaceful company to skulls, signs, screaming faces, people making faces, animals and action.

A naked woman tied to a post (“Gloria”) is set free in the “Act of Liberator”; it then runs in her glorious nakedness next to masked demonstrators and smoke from tear gas.

“The Broken Dream” is more of a “broken” face — puckered, sleepy, hovering over a barely sketched nude body with three crescent-looking faces in three different colours.

Oneiric, staring at the viewer, challenging him to read their thoughts or feelings, the faces in Azza’s works are often impassable or ambiguous; without the title giving away their meaning, they would be inscrutable, adding to the dream-like quality of his art.

The artist’s first show was in 1967 at Tetouan. Since then, he has exhibited in Tangier, Brussels, Belgrade, Munich, Solinger, Dusseldorf, Koln, Offenbach, Amsterdam and Tunis, and participated in group exhibitions in Yugoslavia, Norway, Switzerland, Belgium, Iraq, Tunisia, Germany, Poland, the UK and US.

He was awarded several prizes in international competitions in Europe and the US.

The works will be on display until December 20.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The Mobile Atelier Society, in cooperation with the Kudsi Association Knowledge for Heritage and Culture, has launched an art exhibi

Artists from Jordan and Japan ask piercing, contemplative questions while celebrating cultural exchange at Dar Al Anda Art Gallery’s “East to East” exhibition.

AMMAN — “An ‘Easternised’ Scandinavian”: this is how an art critic described the Danish painter Bente Christensen-Ernst, whose latest work i