You are here

If buildings could tell their stories

By Sally Bland - Mar 08,2015 - Last updated at Mar 08,2015

Golda Slept Here

Suad Amiry

Doha: Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation, 2014

Pp. 201

Having already published several excellent books on different aspects of Palestinian reality, Suad Amiry finally turns to her own field: architecture. The setting and subject matter of “Golda Slept Here” are the beautiful old Palestinian homes in the part of Jerusalem that was occupied in 1948, now dubbed West Jerusalem. Yet her approach to these houses is more than professional: “What truly interested me in a building, a place, or a country were the stories that lay behind them, or in this case under them... if only buildings could tell their stories.” (pp. 79 and 19)

The book’s title is a reference to the Bisharat mansion which was commandeered as the residence for none other than the late Israeli prime minister, Golda Meir. The title, “Golda Slept Here”, also signals that Amiry is continuing her characteristic style of intertwining the personal and the political, and packaging both in biting humour and irony. If there is any doubt about the irony that invades Palestinian lives, the subtitle — “Palestine: the Presence of the Absent” — says it all. The book is brimming with people who are fully present in this world, many of them in Palestine, but whom draconian Israeli laws render “absent” in order to deny them access to their homes and property.

Amiry was inspired by the Nakbeh Survivors Silent March, commemorating 60 years since the majority of Palestinians was displaced. In May 2008, 100 participants followed 10 Palestinian owners to their mansions and villas in Talbiyah, while the current Israeli occupants watched “from behind curtains and the big and small windows of those same houses. The intolerable pain of one and the fear of the other have haunted me ever since, and pleaded with me to become the topic of my book”. (p. 4)

To complete her research for this book, Amiry had to sneak into Jerusalem, where she would probably have been born were it not for the Nakbeh, and where her friend, Huda, is waiting to give her a tour of “the biggest real estate robbery in modern history”. (p. 23)

The tour adds to Amiry’s collection of stories about how individual Palestinians were driven from their homes, what they remember of them, and how they have tried to return. There is indeed much pain, but also incredible love, persistence and daring.

The story of architect Andoni Baramki’s love for his home has an almost fairy-tale quality but without the happy ending. Builder of some of the most beautiful and durable structures in Jerusalem neighbourhoods like Musrara, Katamon and Baq’a, Baramki and his family were expelled from the house he loved most in 1948.

Keeping watch over it for two decades across the armistice lines, he went with a pile of documents and a smile on his face to the Israeli courts after the 1967 war, only to learn that he was a “present absentee” and thus barred from living in it. To complete the irony, his son, Gabi Baramki of Bir Zeit University, was later to visit it reinvented as an Israeli museum.

With Huda Al Imam and Nahil Aweidah, who are cousins, Amiry sneaks from East to West Jerusalem to visit the Aweidah family home which Amidar, the Israeli government agency entrusted with “absentee” property, is planning to sell. They also see the Palestine Broadcasting building where Amiry’s father once worked, Villa Harun Al Rashid where Golda Meir lived in the 1960s, and Huda’s family house in the Greek Colony which she regularly visits to honour a promise made to her father years before.

Their seemingly harmless tour is something of an adventure: Huda is jailed for the day, and threatened with deportation for repeatedly “bothering” the Israeli family who now occupies her family’s home. Amiry must scurry away for she has entered Jerusalem “illegally”.

Such visits inevitably evoke detailed, emotion-laden memories of the day people were expelled from their homes, and their pre-war lives. This is Amiry’s real focus. She is trying to break the Palestinian habit of speaking in the collective “we”, while avoiding, due to shyness, fear or unresolved pain, “the very personal story of being thrown out of her or his home, living room, or bedroom”. (p. 172)

Amiry doesn’t claim to be free of the “we” syndrome, but admits to not having dared visit her father’s original home in Jaffa. Nor in all her conversations with Um Salim, as recorded in “Sharon and My Mother-in-Law”, did she ask her about leaving her home — a gap rectified in this book.

Remembering the personal side of the story and sharing memories is important, not only for hanging on to Palestine, but for hanging on to one’s self and to normality which, among all that Israel has stolen from the Palestinians, is what Amiry protests the most. “Golda Slept Here” is a giant, creative step towards overcoming the “we” syndrome; hopefully, others will add their stories.

Related Articles

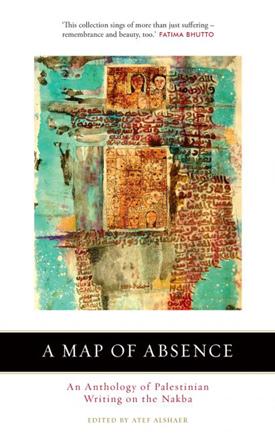

A Map of Absence: An Anthology of Palestinian Writing on the NakbaEdited by Atef AlShaerLondon: Saqi BooksPp.

For Suad Amiry, the life-long goal has been to document, restore and protect 420 Palestinian villages in the West Bank, Jerusalem and Gaza.I

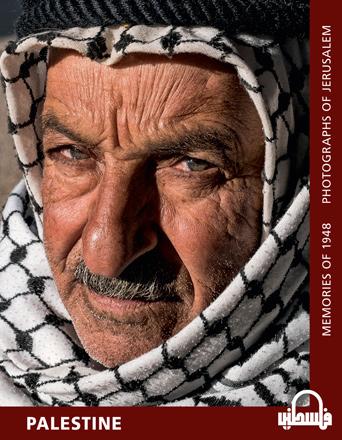

Palestine: Memories of 1948, Photographs of JerusalemChris Conti and Altair AlcantaraTranslated from French by Isabelle LavigneLondon: Hespe