You are here

Idiosyncratic, diverse creativity

By Rand Dalgamouni - Feb 18,2015 - Last updated at Feb 18,2015

AMMAN — The world of artist Emily Jacir is that of depth, intensity, dogged determination, serious questions and also a tinge of dark humour.

The versatile award-winning artist explores probing themes — such as identity, displacement, translation and loss — in installations, interventions, videos and various works of art on display at Darat Al Funun.

Although the plight of the Palestinian people plays prominently into her work, Jacir’s art reaches even farther. She looks for individuality in a sea of enforced stereotypes.

The sprawling exhibition — titled “A Star is as Far as the Eye Can See and as Near as My Eye is to Me”, a poem by Beat Generation poet Gregory Corso — encompasses work from the late 1990s until 2013 and offers a unique look at the artist’s idiosyncratic, diverse creativity.

In “Change/Exchange”, a work of performance art from 1998, Jacir took $100 and exchanged it into French francs, and vice versa over and over again, until all she was left with was some meagre change.

The exhibition shows pictures of the exchange shops, their receipts and the end result.

Fascinating in its simplicity, the work hints at the trajectories that Jacir says she is most interested in, such as transformation and “what’s lost, [and] what’s gained when people move from one place to another”.

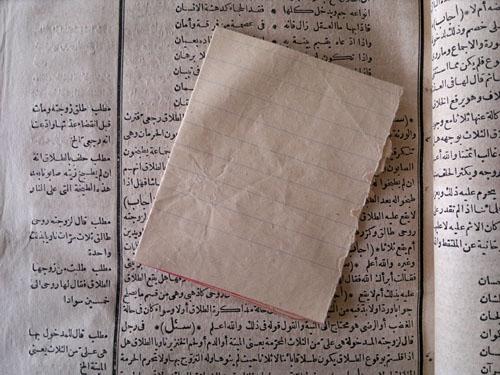

Scattered around the complexes of Darat Al Funun are murals of dedications from three of 6,000 books that had belonged to Palestinian homes, libraries and institutions before they were taken by Israelis and classified at the Jewish National Library Jerusalem as “Abandoned Property”.

The books are all that remains of some 30,000 books lost in the creation of Israel in 1948 and the looting of Palestinian property.

Between 2010 and 2012, Jacir photographed the books using her cell phone, and the results make up the installation “ex libris”.

A simple inscription like “this book was rewarded to student Hanna Boulos for his perfect attendance at school” becomes proof of presence and ownership, and a poignant glimpse at lives long lost in the atrocities of the occupation.

In her interventions, Jacir’s work can be — in her words — “guerrilla-like”.

A case in point is the “Xmas Intervention”.

In 1999 and 2000, the artist designed and printed Christmas cards to “reclaim the image of Bethlehem from commercial hype”.

She then “secretly” added her cards to the stocks of Christmas greeting cards at New York City stores to show the general public, “unsuspecting shoppers”, what is actually happening in Bethlehem, Nazareth and Jerusalem.

The artist left her name and e-mail on the cards, and has received messages of thanks from some “unsuspecting shoppers” who asked for more information about what Palestinians face every day.

In “Sexy Semite”, Jacir asked 60 Palestinians living in New York to place personal ads in a free weekly publication seeking Jewish mates to return home through Israel’s “Law of Return”.

“I wanted to pollute the space of the personal ads section, so that one issue of ‘The Village Voice’ personal section would be full of Palestinians looking for mates,” she writes.

Participants were asked to describe themselves as “Semite” to disrupt the narrative that only associates the word with Jews.

Jacir did the intervention in 2000, 2001 and 2002, when the media finally noticed and mistook it for a terrorist threat.

The ads give a twisted sense of humour to the displacement of Palestinians, who are now looking for Jewish spouses to “legitimise” their right to return to their homes.

In one such ad, a “leggy, small-waisted Semite with Cleopatra eyes” is seeking “a tall, sexy, Jewish male to live in Jerusalem and spend weekends on Tel Aviv Beach”.

In “Burj Al Riyadh” and “Al Riyadh”, Jacir and Yazid Anani set up two billboards in Ramallah in 2010 proposing two fictional projects, with words cheekily referring to “the dream” of living in the heart of Old Ramallah “on the rubble” of the city’s historical centre.

A glossy picture of modern houses promises “intensive security” in Al Riyadh residential suburb, while the description of a project “to destroy” Ramallah’s historical vegetable market are splashed over a rendition of “Al Riyadh Tower”.

Jacir says the billboard advertising a gated community was met with anger by Ramallah Taht residents, who ended up defacing it; while the advertisement of Al Riyadh Tower was met with apathy.

Fifteen years later, the artist laments that the “neoliberal project is marching on” in Ramallah, with such plans now not far from reality.

It is easy to lose oneself in the major works on display at Jacir’s expansive exhibition, but a closer look at the simpler pieces is also rewarding.

In “From Paris to Riyadh (drawings for my mother)”, the artist extracted and collected “the illegal sections” showing exposed parts of female bodies from Vogue magazine issues between 1977 and 1997.

The parts are all blacked out, as Jacir recreated an action her mother used to do every time she flew into Saudi Arabia when the family was living there.

Dark silhouettes, half-arms, necks, shoulders and barely recognisable body parts are spread on transparent sheets in this awkward space where women as objects and women as taboos converge.

A must-see is “Today, there are four million of us”.

The installation shows a reprint of “Mural of a Refugee” brochure from the Jordanian Pavilion of the 1964 World’s Fair, which was held where the Queens Museum of Art now stands in New York.

It is accompanied by all the research Jacir conducted on the pavilion.

She discovered the brochure at the museum’s archive and had known about the pavilion from her mother, who was among the hostesses who distributed the brochures at the time.

The mural, by veteran Jordanian artist Muhanna Durra, generated controversy at the fair.

US Jewish groups said the poem in the mural was “anti-Semitic”, with some picketing the pavilion and calling for its removal, but the fair’s director, Robert Moses, “did not cave in”, according to Jacir.

The section dedicated to the pavilion is an important record of Jordan’s art history and the major role that Palestine continues to play in it.

For Jacir, showing such a wide breadth of her work in Jordan is also important.

“This is such a central place for us as Palestinians,” she says.

“It’s really an exciting place… anything can happen here — in a positive sense.”

The exhibition continues until April 23.

Related Articles

In the Wake of the Poetic: Palestinian Artists after DarwishNajat RahmanNew York: Syracuse University Press, 2015Pp.

AMMAN — Annemarie Jacir started her career writing and editing scripts, but cinema soon caught her interest and she started producing films

AMMAN — Darat Al Funun — Khalid Shoman Foundation is currently showing a collection of artworks in solidarity with Palestine from the 1970s