You are here

Funnyman Robin Williams gave comedy a darker edge

By Agencies - Aug 12,2014 - Last updated at Aug 12,2014

LOS ANGELES — Oscar-winning actor Robin Williams shot to fame for his madcap standup act and his offbeat alien Mork, but his most famous roles showed a depth of pain behind the comedian’s mask.

The wildly popular 63-year-old funnyman, whose career spanned almost four decades, was known for rapid-fire, stream-of-consciousness improvisations and impersonations.

On screen, his characters were often offbeat and eccentric — from the zany alien Mork from the planet Ork, the television role in the 1970s that first catapulted him to fame, to the divorced dad who transforms himself into a elderly British nanny in Mrs Doubtfire.

His skill at imitating voices was often showcased — as in his portrayal of the genie in the 1992 Disney adaptation of “Aladdin”, in which his character runs through a string of celebrity impressions.

But he also found success in darker roles, including an Oscar-winning turn as psychologist Sean Maguire, a Vietnam veteran and widower who counsels troubled genius Will Hunting.

‘I was shameful’

But for all Williams’ Hollywood success and outsize public persona, the comedian faced private demons, including recurring battles with drugs, alcohol and mental illness.

He quit drinking and cocaine in the early 1980s, when his first son was born, but after 20 years sober, he started drinking again while filming in Alaska in 2003, he told the Guardian newspaper in 2010.

“It was that thing of working so much, and going ‘Fuck, maybe [drinking] will help?’ And it was the worst thing in the world,” he told the newspaper, adding, however, he did not start taking drugs again.

It took him another three years to get back to sobriety, after a family intervention led him to rehab, he said, blaming his drinking for the break-up in 2008 of his 19-year-second marriage.

“You know, I was shameful, and you do stuff that causes disgust, and that’s hard to recover from.”

It was health problems — and open heart surgery — in 2009 that he credits with being the true turning point.

“It breaks through your barrier, you’ve literally cracked the armour. And you’ve got no choice, it literally breaks you open. And you feel really mortal,” he said.

During the three-hour surgery, doctors replaced Williams’ aortic valve, repaired his mitral valve, and corrected an irregular heart beat.

The actor was also reportedly diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and in July 2014, he checked into a Minnesota rehab facility for help maintaining sobriety after a gruelling year-and-a-half of work.

A darker side

One of Williams’ most famous roles was as radio disk jockey Adrian Cronauer, whose loud and drawn out “Gooooooood morning, Vietnaaaaaam” started each broadcast and was the title of the film.

The character bucks authority on the air, bringing US troops the 1960s rock music and lifestyle they missed from home, playing unapproved songs and riffing in quick-fire improvisations in between.

Although he brings humour to his portrayal of the character, the film, set amid one of the longest and deadliest US wars abroad, is hardly a comedy.

And even his more light-hearted films touch on deeper sadness, including slapstick “Mrs Doubtfire”, the cross-dressing character created by divorced dad Daniel Hillard in desperation to see his kids, who were living with a wife who sees him as irresponsible.

Williams was beloved as inspirational prep-school teacher John Keating, in the “Dead Poets Society”, another character that defied authority with an unorthodox teaching style that ultimately gets him fired.

And in yet another dramatic role in “Awakenings”, Williams played Malcolm Sayer, a doctor with a ward full of catatonic patients.

Sayer finds success with a treatment, shepherding his newly awakened charges into an unfamiliar world decades after their mental freeze, but it is ultimately temporary.

But Williams left behind his darker side in films for children, including as the voice behind the genie in Disney’s “Aladdin”, singing the iconic, and award-winning, song “Friends Like Me”, and in kids’ romp “Jumanji” about a board game that comes to life.

The question from a fan in a Sirius XM interview last year was innocent — what do you think you’d be doing if you didn’t become a comedian? — and within seconds Robin Williams was impersonating physicist Stephen Hawking getting a lap dance at a strip club.

“Now don’t sit on the keyboard!” Williams said, coaxing laughs from a few dozen people in a Manhattan studio.

How did he get there? Explaining it would take twice as long as it took to actually happen. Would anyone else in the world have made such a leap?

Not a chance. Williams, who died in an apparent suicide Monday, was a comic force of nature. The world got to know him as the wild alien in “Mork & Mindy”, a comedian who elevated improvisation to an art form and also demonstrated a rare versatility in more serious roles. He moved seamlessly from comedy to drama to tragedy to comedy again during a Hollywood heyday in the 1980s and 1990s. His Academy Award as a supporting actor in “Good Will Hunting” came in a drama.

In 1997, Entertainment Weekly magazine named Williams the funniest man alive, and the very next year listed him as one of the world’s 25 best actors — a double distinction that made him rare, if not unique.

He touched every generation and demographic, making his entrance in a 1970s comic generation with Steve Martin, John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd and Billy Crystal. He exploded onto the scene at a time when two schools of comedy dominated — “Saturday Night Live” and Johnny Carson — and Williams felt equally comfortable running with both crowds.

On a stage, in front of the lights, is where Williams shined most brightly. The riffs, tangents and impersonations came rushing at the audience, a seemingly endless torrent. It looked like onstage cocaine, a drug he abused in real life and, of course, made part of his comedy.

“Cocaine is God’s way of telling you you are making too much money,” he would say.

On a television talk show, hosts knew Williams barely needed to be wound up. Sometimes, he needed only an audience of one: Williams visited Christopher Reeve a week after the actor’s horseback riding accident, dressed in scrubs with a surgical mask and speaking in a Russian accent.

The roles became less prominent as he aged and a different generation took the spotlight. Last year CBS cast him as the star of a sitcom, “The Crazy Ones”, in which Williams played the colourful elder statesman at a New York ad agency. The network had high hopes for the comedy, which also starred Sarah Michelle Gellar, but they quickly faded and the show was cancelled after one season.

That didn’t make Williams unique — Michael J. Fox also failed in a recent return to television — but it was an indication that Williams was no longer a sure ticket to success.

Like many comedians, Williams often seemed driven by demons. He had a complicated personal life, suffered from depression and was treated for substance abuse, most recently earlier this summer. He did a few lines of cocaine with John Belushi on the last night of that comic’s life.

A darkness seeped in during an interview with comedian Marc Maron in 2010, where Williams seemingly dismissed what would be a career highlight for many actors. “People say you’re an Academy Award winner,” he said. “The Academy Award lasted about a week and then one week later, people went, ‘Hey Mork!’”

Stand-up comedy was where Williams got the most satisfaction.

“You get the feedback,” Williams said in a 2007 interview with The Associated Press. “There’s an energy. It’s live theatre. That’s why I think actors like that. You know, musicians need it, comedians definitely need it. It doesn’t matter what size and what club, whether it’s 30 people in the club or 2,000 in a hall or a theater. It’s live, it’s symbiotic, you need it.”

In the 2013 Sirius appearance with Whoopi Goldberg, his comic colleague had no trouble encouraging a visit from Elmer Fudd, one of the many voices Williams could instantly slip into.

Instantly, “Elmer” was singing Bruce Springsteen: “I’m dwivin’ in my car...”

Ultimately, Williams had needs no one could meet. The millions of people he made laugh over nearly four decades in the public consciousness weren’t enough.

Related Articles

Robin Williams’s death had people worldwide scouring the Internet for insights into the famed comic’s life, making him the hottest search trend of the year on Google, the web giant said Tuesday.

LOS ANGELES — Actor Will Smith offered apologies on Monday to Chris Rock for smacking the comedian during the Oscars ceremony, as the body t

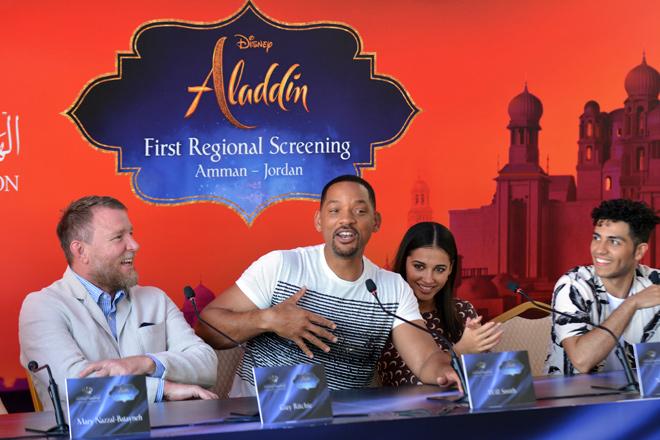

AMMAN — Just as he walked into Wadi Rum, actor Will Smith envisioned how to infuse his awe-inspiring experience into the character he is pla