You are here

Four Generations of Koreans in Japan

By Sally Bland - Jan 06,2019 - Last updated at Jan 06,2019

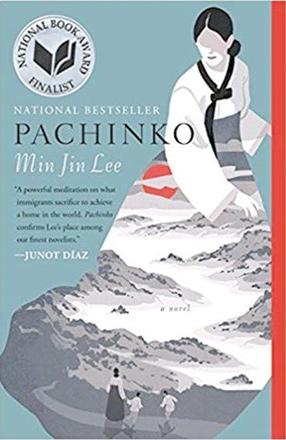

Pachinko

Min Jin Lee

New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2017, 479 pp

Pachinko, a cross between slot machine and pinball, gives its name to this novel, but the word does not even appear until half way through the book.

At first, one does not understand why Korean-American writer Min Jin Lee chose this form of gambling as the title. Instead, family, survival and being part of a despised immigrant minority seem to be the salient themes of this story, which stretches from 1910, when Japan annexed Korea, until 1989. Other themes include tradition and transition, how Christianity impacted on Korean lives, and last but not least, love — whether love of family or romantic love.

In this family saga of four generations, only one character who appears in the first chapter survives until the last. This is Sunja, who starts off as a shy, hardworking girl in a Korean fishing village, only to become the matriarch of the family.

At 16, Sunja does something seemingly out of character: She has an affair with Hansu, an older man, and gets pregnant, setting the stage for all the subsequent happenings in the novel. Hansu cannot marry Sunja, as he is already married, but he promises to take care of her and the child. However, she is too proud to accept his offer.

By a stroke of good luck, Isak, a Christian minister, comes to stay at her mother’s boarding house and agrees to marry her and give his name to the child. He is on his way to Japan, to join his brother and work in a church there.

This will rescue Sunja from shame, so she joins him and sees cars and modern buildings for the first time. They settled in with Isak’s brother and his wife in the Korean ghetto in Osaka, but things will not be easy as dire poverty, World War II and the stigma of being Korean in Japan all take their toll.

Different members of the family adopt different survival strategies, balancing between a desperate need for money and the moral high ground, from selling food in the open market, to getting an education, to working in a factory, to learning Japanese well and mimicking Japanese habits.

One stands in awe of how hard they work, what they must endure, their stoicism, but whatever they do, it is not enough to be accepted.

Wealth only accrues to the family from Sunja’s son who buys into pachinko parlors, but this does not gain them respect, as the game is associated with gangsterism. Years later, when those of the family who survived are well-off, they still have to get a foreigners’ ID.

As Sunja’s grandson, Soloman, is told by his boss in 1989: “It’s not like Koreans had a lot of choicesin regular professions… Maybe your dad could have worked for Fuji or Sony, but it wasn’t like they were going to hire a Korean, right?… Japan still doesn’t hire Koreans to be teachers, cops and nurses in a lot of places… It’s crazy what the Japanese have done to the Koreans and the Chinese who were born here.” (p. 444)

For many years, the author wanted to write about Koreans in Japan, but she did not feel she knew enough. All that changed when her husband got a job in Tokyo and they moved there for some years.

As much as one learns about the Korean Japanese, the most outstanding aspect of Min Jin Lee’s writing is her ability to quickly switch point-of-view from one character to another. This means that none of the characters are mere symbols. Rather they are all fullblown and one knows their opinions and feelings on all the vital things in life, from those who advocate Christian love to those who believe one must fend for themselves.

Though Sunja seems quite pragmatic and stoic, her inner thoughts are often in turmoil; there is much she cannot completely share with anyone, particularly her feelings for Hansu, who continues to pop up in her life, usually to help her or their son, Noa, in times of crisis.

When she sees him at her mother’s funeral, Sunja remembers how “her mother had said that this man had ruined her life, but had he? He had given her Noa; unless she had been pregnant, she wouldn’t have married Isak, and without Isak, she wouldn’t have had Mozasu and now her grandson Solomon.

She didn’t want to hate him any more.” (p. 421) She often wonders if people should have only one person in the life.

One cannot help but notice in the story that it is mostly the women who, though lacking in resources except for their own hard work, are flexible and determined enough to survive.

Related Articles

Japan’s once-booming pachinko industry, grappling with a greying customer base and the threat of new competition from casinos, is adopting a softer touch and smoke-free zones to lure a new generation of players, particularly women.

BUSAN, South Korea — The rise of South Korean diasporic cinema — characterised by films like Lee Isaac Chung’s “Minari” and Justin Chon’s “J

By Jung Ha-won SEOUL — Trying to raise the world’s lowest birth rate is among the missions of South Korea’s welfare ministry — a challe