You are here

Fossil jaw sheds light on turning point in human evolution

By AP - Mar 15,2015 - Last updated at Mar 15,2015

NEW YORK — A fragment of jawbone found in Ethiopia is the oldest known fossil from an evolutionary tree branch that eventually led to modern humans, scientist reported Wednesday.

The fossil comes from very close to the time that the early human branch split away from more ape-like ancestors best known for the fossil skeleton Lucy. So it gives a rare glimpse of what very early members of our branch looked like.

At about 2.8 million years old, the partial jawbone pushes back the fossil record by at least 400,000 years for the human branch, which scientists call Homo.

It was found two years ago at a site not far from where Lucy was unearthed. Africa is a hotbed for human ancestor fossils, and scientists from Arizona State University have worked for years at the site in northeast Ethiopia, trying to find fossils from the dimly understood period when the Homo genus, or group, arose.

Our species, called Homo sapiens, is the only surviving member of this group.

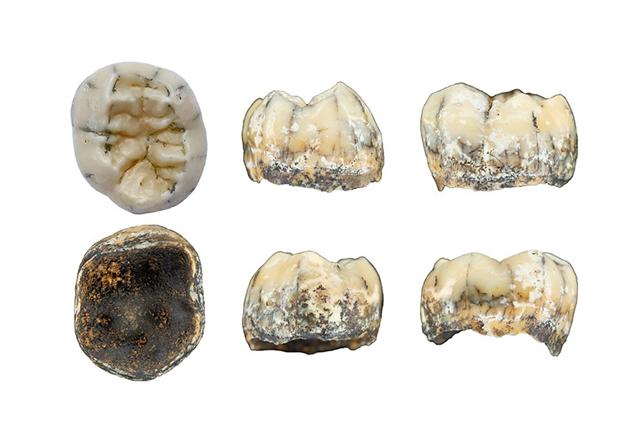

The jaw fragment, which includes five teeth, was discovered in pieces one morning by Chalachew Seyoum, an Ethiopian graduate student at Arizona State. He said he spotted a tooth poking out of the ground while looking for fossils.

The discovery is described in a paper recently released by the journal Science.

Arizona State’s William Kimbel, an author of the paper, said it’s not clear whether the fossil came from a known early species of Homo or whether it reveals a new one. Field work is continuing to look for more fossils at the site, said another author, Brian Villmoare of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Analysis indicates the jaw fossil came from one of the earliest populations of Homo, and its age helps narrow the range of possibilities for when the first Homo species appeared, Kimbel said. The fossil dates to as little as 200,000 years after the last known fossil from Lucy’s species.

The fossil is from the left lower jaw of an adult. It combines ancestral features, like a primitive chin shape, with some traits found in later Homo fossils, like teeth that are slimmer than the bulbous molars of Lucy’s ilk.

Despite that mix, experts not involved in the paper said the researchers make a convincing case that the fossil belongs in the Homo category.

And they present good evidence that it came from a creature that was either at the origin of Homo or “within shouting distance”, said Bernard Wood of George Washington University.

The find also bolsters the argument that Homo arose from Lucy’s species rather than a related one, said Susan Anton of New York University.

The new paper’s analysis is first-rate, but the fossil could reveal only a limited amount of information about the creature, said Eric Delson of Lehman College in New York.

“There’s no head, there’s no tools, and no limb bones. So we don’t know if it was walking any differently from Australopithecus afarensis,” which was Lucy’s species, he said.

It’s the first time that anything other than isolated teeth have turned up as a possible trace of Homo from before 2.3 million years ago, he said.

“This fills a gap, but it hasn’t yet given us a complete skeleton. It’s not Lucy,” Delson said. “This is always the problem. We always want more.”

Also on Wednesday, another research team reported in a paper released by the journal Nature that the lower part of the face of Homo habilis, the earliest known member of the Homo branch, was surprisingly primitive. That came from reconstruction of a broken jaw that was found 50 years ago.

The finding means the evolutionary step from the Ethiopian jaw to the jaw of Homo habilis is “not so large”, said an author of the Nature study, Fred Spoor of University College London and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

Related Articles

Scientists working in Kenya have unearthed the oldest known stone tools, simple cutting and pounding implements crafted by ancient members o

PARIS — An "obsession" with the lower jaw of a long-dead human, unearthed in the 1960s at a prehistoric Moroccan campsite, led palaeoanthrop

PARIS — A child’s tooth at least 130,000 years old found in a Laos cave could help scientists uncover more information about an early human