You are here

A collective memoir

By Sally Bland - Sep 11,2018 - Last updated at Sep 11,2018

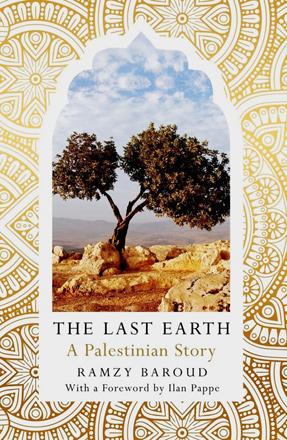

The Last Earth

Ramzy Baroud

UK: Pluto Press

Pp. 272

Many books have been written about Palestine and the Palestinians. Nonetheless, Ramzy Baroud’s new book stands out as unique. For those familiar with Baroud’s analytical writing, “The Last Earth” has the same precision and clarity of language found in his columns, and the same adherence to fact, but it is written with all the pathos and lyricism of fiction. Drawing inspiration from Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry, the title of “The Last Earth” is such an obvious metaphor for what Palestinians are seeking but seldom find — a safe place to which they can always return, a homeland.

“The Last Earth” is based on oral history and the idea of “history from below”, recounting the life stories of eight Palestinians from different generations and different parts of Palestine or places of exile. Several years ago, Baroud and his co-researchers issued a call for Palestinians everywhere to share their stories. Fifty of the hundreds who responded were interviewed; finally, eight particularly vivid and representative stories were chosen for inclusion in the book, told by Baroud in compelling prose.

By beginning with the story of a young man and woman who had no choice but to flee the battle in Yarmouk camp and risk the perilous passage to Europe, the book reminds that the Nakba —Palestinian displacement and dispossession — is ongoing. Braving the Mediterranean Sea and well-fortified European borders is the contemporary Palestinian exodus. This first story is also daring in describing the love affair that grew between the two young people as they volunteered to help the wounded in the camp’s Palestine hospital: “The overpowering chemistry they instantly felt transcended the gore around them as they both stood defenceless in front of their unexpected emotions.” (p. 16)

Another story describes the valiant, though ultimately futile, attempts of the fellahin in villages north of Gaza to protect their land and families in 1936 and again in 1948. A subsequent story highlights how refugee women shouldered innumerable tasks after the 1967 occupation when “most of the men disappeared into the gorge of gruelling labour in Israel” and women were left to manage virtually everything. (p. 94)

A more contemporary story features a family in Burqin in the northern West Bank, whose members have consistently resisted the occupation whether as fedayeen in the mountains or political prisoners on a hunger strike. Each story encompasses the extended family of the main subject, showing generational changes, new gender roles and successive historical stages. While one knows that such Palestinians exist, it is seldom if ever one gets such an intimate portrait of their background, convictions and feelings. The book serves the purpose of a collective memoir.

These are the stories of unsung heroes and lesser known massacres and destroyed villages. They are stories of seemingly unresolvable dilemmas and new paths charted, such as that of Umm Marwan, a Gaza mother. “Two opposing forces lived within her: an unfamiliar sense of responsibility towards a revolution she hardly understood and her cultural socialization where women were taught that their place was in the home and not the battlefield… But there was something that she did well and which she did fearlessly. In wedging herself between screaming children and angry soldiers, she found her calling.” (p. 104)

There are also unsolvable dilemmas like the case of Ali whose story is told via the letters he writes to his daughter from whom he has been involuntarily separated. Totally emblematic of the Palestinian cause, he has no “last earth” where he can live with his family, after fighting for Palestine all his life.

The way the stories are told makes it clear that the intent is not to arouse pity but to elicit recognition of Palestinians as people deserving of being in control of their lives and not subject to the interests and whims of their coloniser and world powers. In Baroud’s words, “the book tells the story of a people whose history cannot be reduced to a timeline of conflict, but rather is embroidered and torn with complex human emotions, hopes, dreams, struggles, and priorities that seem to pay no heed to politics, the military balance, or ideological rivalries”. (p. 266)

Despite the diversity and individuality of the respective stories, there is an essential common strain as a result of Zionist policy against the Palestinians. As Ilan Pappe points out in the foreward: “The uniformity of this Palestinian experience throughout the years… turns the Palestinian memory, oral history, and recollection into not just a registry of atrocities but also tools of cultural resistance.” (p. xiii)

Baroud’s book excels in its honesty. Though extolling the positives of pre-48 Palestine, it is not presented as a paradise as in some nostalgic accounts; nor are all Palestinians presented as heroes. Several of the stories include a class aspect, as when fellahin had to fend off attempts by big clans in their area to take over their land and keep them in a state of near-slavery. Some stories note people’s feelings of betrayal by the leadership, then and now.

Baroud has turned Palestinian history into a page turner without sacrificing truth or integrity. “The Last Earth” is exciting and enlightening as it gets to the heart of the refugee experience in an unprecedented way, showing the full range of Palestinians’ humanity. It is a persuasive, literary argument for why Palestinians deserve to be free in their own country.

Related Articles

In the Wake of the Poetic: Palestinian Artists after DarwishNajat RahmanNew York: Syracuse University Press, 2015Pp.

Yusif Sayigh: Arab Economist, Palestinian Patriot — A Fractured Life StoryEdited by Rosemary SayighThe American University in Cairo Press, 2

A Map of Absence: An Anthology of Palestinian Writing on the NakbaEdited by Atef AlShaerLondon: Saqi BooksPp.