You are here

‘Severe criminal justice policies hurt US economy’

By Agencies - Apr 24,2016 - Last updated at Apr 24,2016

WASHINGTON — Longer prison sentences for non-violent criminals and crowded prisons are hurting the American economy more than they are helping it, economists in US President Barack Obama's administration said in a report released on Saturday.

The prison population in the United States is 4.5 times larger than it was in 1980, primarily driven by longer sentences and higher conviction rates for nearly all offences, according to the report.

Economists are "of one mind" that packed prisons, excessively long sentences, and insufficient reentry programmes "are counterproductive to our economy as a whole in addition to hurting the people involved", Jason Furman, the chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, told reporters in a call on Friday.

Administration officials, economists, business leaders, and scholars will discuss on Monday the council's findings at an event hosted by the White House, the American Enterprise Institute think tank, and New York University's Brennan Centre for Justice.

The United States can reap greater economic benefit through investments in police, prisoner education and job opportunities for ex-prisoners than it can from putting additional funding towards prisons, the council's report said.

The council's report was based on a review of existing economics research, and does not estimate the indirect costs borne by the US economy as a result of its current criminal justice policies.

Later this year, the Brennan Centre will unveil a study quantifying how much the US criminal justice system costs Americans in terms of employment, wages and gross domestic product, said the centre's director of justice programmes, Inimai Chettiar.

Previous administrations have not brought the same focus to how criminal justice policies affect the US workforce, said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, who led the Congressional Budget Office from 2003-05 and is now president of the American Action Forum think tank.

Since the recession of the late 2000s, "every aspect of the workforce has been scrutinised more closely, and this sort of popped out", he told Reuters.

Separately, a major study of income and life expectancy found that the richest Americans tend to outlive the poorest by almost 15 years, and that gap has grown since 2001.

The findings, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, were based on more than 1 billion tax records from 1999 to 2014, as well as government mortality statistics.

The gap in life expectancy between the richest 1 per cent and the poorest 1 per cent was 14.6 years for men and 10.1 years for women, indicated the study led by Raj Chetty, an economics researcher at Stanford University.

"For example, men in the bottom 1 per cent of the income distribution at the age of 40 years in the United States have life expectancies similar to the mean life expectancy for 40-year-old men in Sudan and Pakistan," it said.

The inequality in life expectancy also increased over time.

"There was a larger increase in life expectancy for higher income groups during the 2000s," added the study.

The rich tended to live even longer, by more than two years for men and almost three years for women between 2001 and 2014.

"Life expectancy did not change for individuals in the bottom 5 per cent of the income distribution," it continued.

According to researchers, factors found to affect life expectancy among the poor included smoking and obesity.

Where people lived also made a difference.

The shortest life expectancies in the lowest income groups were seen in Nevada, Indiana and Oklahoma — 77.9 years — while the longest-lived among the poorest Americans were in New York, California and Vermont — 80.6 years.

The average life expectancy in the United States is 78.8 — 81 for women and 76 for men, according to the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

Related Articles

GENEVA — The UN called on Tuesday on Iran to immediately release human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh and other political prisoners who have

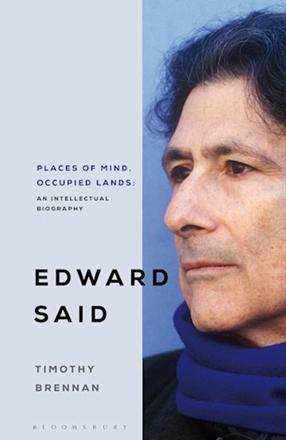

Much has been written about Edward Said, but this is the first comprehensive biography in English of the renowned scholar, covering his personal, professional and political life. The author, Timothy Brennan, teaches in the humanities at the University of Minnesota and has written several scholarly books on world literature, making him well-informed on subjects close to Said’s heart. Brennan is obviously an admirer of Said but the book does not simply sing his praises. Rather, it is a critical review of the development of his thinking, writing, and influence over the years.

BAGHDAD — Iraqis on Wednesday were outraged, heartbroken but not surprised to hear US President Donald Trump had pardoned for four Blackwate